By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, May 31, 2018)

The U.S. may be on the brink of one of the greatest foreign policy achievements in its post-WWII history. As of today, I’d say the chances President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un agree to any substantive plan to denuclearize the Korean Peninsula are slim, though not zero.

But hope is eternal and even Trump’s sometimes erratic behavior is now being viewed by some of his most ardent critics as an asset in dealing with North Korea.

“A volatile negotiating style is sometimes a sign of an inexperienced or uncertain bargainer,” opines Washington Post columnist David Ignatius. “But it’s Trump’s approach, and however bizarre the route, he’s nearing a diplomatic breakthrough.”

Its obviously too soon to put North Korea’s denuclearization on the list of major U.S. foreign policy achievements. But, if it should happen, what else would already be on the list since World War II?

I’ve compiled an informal list of the U.S.’s ten biggest foreign policy achievements since WWII. Why ten? I couldn’t come up with an 11th. So forget an honorable mention list.

The criteria for making the list was fairly straightforward. The accomplishment had to represent not just a significant improvement over the past, but a durable achievement. For this reason, Barack Obama’s Iran nuclear agreement did not qualify for this list.

The achievement had to make the U.S. and its allies safer and/or stronger vis-a-vis its adversaries. The strengthening could be economic, militarily or both.

In addition, the U.S. foreign policy achievement’s impact had to be international and not primarily domestic, which eliminated Bill Clinton’s greatest foreign policy achievement: the investment of the ‘peace dividend’ from the collapse of the Soviet Union into America’s technology and innovation economy.

With these informal qualifications, here is my top 10 for the U.S.’s greatest foreign policy achievements since World War II.

Coming in at number 10…

10. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) Treaty of 1948

GATT was a series of multilateral trade agreements designed to reduce trade quotas and tariffs among the treaty’s signatory nations. The first GATT agreement, that included 23 countries, took effect in 1948 and formed the economic foundation for the liberal globalist ideology that dominates today’s world economy.

The agreement itself was not as powerful as many wanted. Yet, President Harry Truman understood the GATT agreement, as weak as it was, would preserve international trade co-operation and become an critical party of U.S. foreign economic and security policy going forward.

Moreover, the 1948 agreement was seen merely an interim measure as there was an expectation the newly-formed United Nations would create an agency to supersede GATT. That never happened. Instead, GATT became the primary tool by which world trade was liberalized and expanded immediately after World War II. It was not until the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995 that was GATT finally replaced.

Up to 1995, GATT’s critical role in the world economy was significant as up to 90 percent of world trade was governed by GATT prior to the WTO.

9. North Atlantic Treaty Organization (1949)

No post World War II agreement had broader implications than the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949. Following the end of the war, the fear of Communist expansion dominated discussions in the West European capitals and, in response to Soviet expansion, the U.S. and 11 Western European nations formed NATO.

The rival Warsaw Pact, created in 1955 by the Soviet Union and its Communist partners in Eastern Europe, formed the basis for what would be the Cold War, which would last until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.

8. Creation of the United Nations (1945)

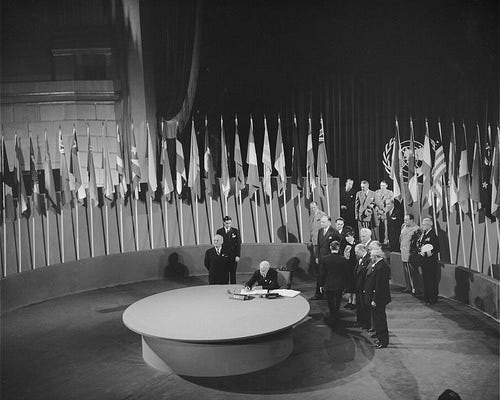

In June 1945, a year after D-Day which lead to the eventual defeat of Germany and the European Axis powers, the United Nations Charter was adopted. Its goals were as profound as the diverse collection of countries sanctioning its existence at the San Francisco Conference in April 1945.

Fifty nations, representing the 80 percent of the world’s population that had just defeated Germany to end the European portion of World War II, met in San Francisco to form an international union predicated on the principle that world wars were an unacceptable means through which to solve international problems.

Even as it was agreed, with considerable dissent, that the “Big Five” (United States, Britain, France, China and Russia) could exercise “veto” powers on any action by the United Nations’ powerful Security Council, the General Assemblyof nations signed onto the United Nations charter knowing its imperfections were far outweighed by its potential.

“The Charter of the United Nations which you have just signed,” said President Truman in addressing the final San Francisco Conference session, “is a solid structure upon which we can build a better world. History will honor you for it. Between the victory in Europe and the final victory, in this most destructive of all wars, you have won a victory against war itself. With this Charter the world can begin to look forward to the time when all worthy human beings may be permitted to live decently as free people.”

On October 24, 1945, the UN officially came into existence. To date, despite its many critics, the UN stands as of the post World War II’s greatest international achievements.

7. SALT I and SALT II Treaties (1972, 1979)

It may seem odd to put SALT and START treaty regimes between the U.S. and Soviet Union ahead of the creation of the UN and NATO, but it is done with some thought. As important as the UN and NATO were in creating institutional frameworks for collectively organizing the common interests of nations, they were band-aids — deeply flawed at their conception and in their application to solve international problems.

Upon the learning in the late 1960s that the Soviet Union had developed a Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) defense system to defend Moscow in case of an all-out nuclear war with the U.S., President Lyndon Johnson met with Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin to start strategic arms limitations talks (SALT).

The elimination of nuclear weapons was (and is) a dream. The SALT discussions therefore focused on the more practical goal of limiting the development of advanced offensive and defensive strategic systems.

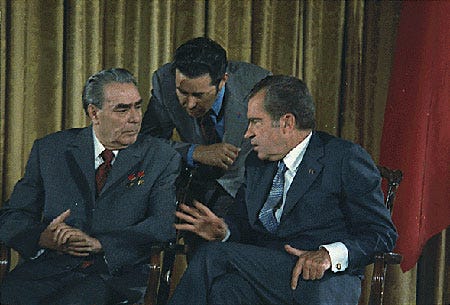

Johnson’s successor, Richard Nixon, took over the SALT talks and on May 26, 1972, in Moscow, he and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev signed an ABM Treaty and an interim SALT agreement.

Starting with Johnson’s initiative and Nixon’s follow through, the U.S. and Soviet Union for the first time decided to limit their nuclear arsenals.

The next round of SALT discussions began immediately after the signing of SALT I with its focus on Multiple Independently Targeted Re-Entry Vehicles (MIRVs) and on June 17, 1979, U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Brezhnev signed the SALT II Treaty in Vienna.

The key element of SALT II was the limitation of both nations’ nuclear forces to 2,250 delivery vehicles and restricting MIRVs, though the treaty itself was never ratified by the U.S. Senate due, in part, to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan in 1979.

Nonetheless, both countries adhered to SALT II’s requirements, even as the next U.S. president, Ronald Reagan, pursued the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START).

6. START I Treaty (1991)

Despite opposition to President Carter’s SALT II agreement with the Soviets, President Ronald Reagan adhered to its restrictions, even as he authorized pursuit of the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), otherwise known as “Star Wars.”

At the same time, Reagan began negotiations for the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START), a bilateral treaty between the U.S. and the Soviet Union that would reduce (not just limit) the number of strategic offensive arms. The first START agreement was signed in July 1991 (taking effect in 1994). START I was the largest arms control treaty in world history and its implementation resulted in the removal of almost 80 percent of all strategic nuclear weapons in the world at the time.

START II was signed by U.S. President George H. W. Bush and Russian President Boris Yeltsin on January 3, 1993, and banned the use of MIRVs on intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). START II, however, never came into effect, even though it was ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1996 and in Russia in 2000. In June 2002, Russia withdrew from the treaty in response to U.S. withdrawal from the ABM Treaty.

START I, however, remains a milestone in the effort to reduce the number of nuclear weapons on the planet.

5. The First Gulf War (1991)

This was the most difficult decision in the list of Top 10 foreign policy achievements. The First Gulf War is the only U.S. military action to make the list and, while successful in its primary goal of removing Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi army from Kuwait, the blowback from this war was significant and could be argued that it continues to this day.

When Saddam Hussein’s Iraq invaded Kuwait in the summer of 1990, President George H. W. Bush faced the this country’s first post-Cold War international crisis. In response, Bush orchestrated a large international coalition to oppose Iraq’s aggression and, following an intensive air campaign in January 1991, launched a land war offensive that drove Iraqi forces out of Kuwait.

President Bush and his foreign policy team built a broad coalition ranging from the NATO allies to a number of Middle Eastern countries. Even Russia, an ally to the Hussein regime, while offering no direct military or material support, diplomatically called for Iraq to leave Kuwait.

The run-up to the war’s start was a model for how diplomatic efforts can work in tandem with military planning; and the effort, as executed by the Bush administration, put the coalition troops in the best possible position to successfully carry out their mission. However, the First Gulf War’s unintended consequences cannot be ignored as they led directly to the rise of Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda and the subsequent attacks against the the U.S. (U.S.S. Cole, 9/11 attacks, etc.)

The U.S. has proven to be good at starting and executing wars — its the ending of wars where the U.S. has problems.

4. Camp David Accords (1979)

As we read the latest events out of the Middle East, it is easy to forget sometimes that a lasting and durable peace between the State of Israel and Egypt has existed, unbroken, since the 1979 Camp David Accords.

Israel and Egypt had fought two (short) wars against each other in the previous 15 years and the prospects for peace seemed unlikely in the midst of a growing Palestinian armed resistance against Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

But, largely through President Jimmy Carter’s personal initiative in bringing two diametrically opposite leaders to the table, a peace agreement was hammered out. Israel returned the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt for security guarantees (that have not since been broken). It was an achievement that still stands as a model for the future.

Carter, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, and Egyptian leader Anwar Sadat, gave us a template and path on how to bring peace to the Middle East (at least on a bilateral basis). The Camp David Accords were without question President Carter’s crowning foreign policy achievement and though peace has not been the rule in the Middle East since the Accords, Israel can rightfully point to a peace treaty with Jordan and a significant thawing of relations with Saudi Arabia as indirect products of the Camp David Accords. Of course, having a common enemy (Iran) is playing a big factor in the new Israel-Saudi detente.

Regardless, the important legacy of the Camp David Accords is unquestionable and is still being written.

3. Cuban Missile Crisis (1962)

On the heals of the Bay of Pigs fiasco in Cuba and a disastrous meeting with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna, Austria, President John F. Kennedy had not earned high marks on foreign policy in his young presidency.

That changed over the course of 13 days in October 1962, and for good reason. His leadership, along with that of his Attorney General, Bobby Kennedy, Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, and U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, Adlai Stevenson, averted the very real potential of a nuclear conflict between the U.S. and Soviet Union. At the very least, a ‘hot war’ was possible, which would have been the first between two nuclear powers.

Screwing up again was not an option for the Kennedy administration in October 1962.

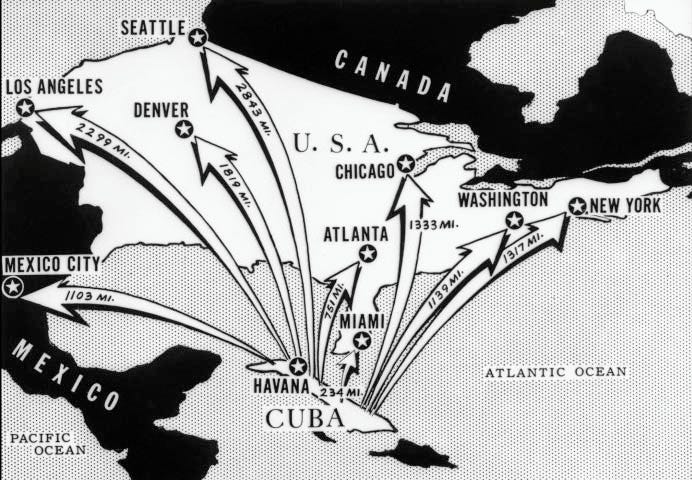

As revealed by U.S. reconnaissance photos, the installation of nuclear-armed Soviet missiles were discovered on Cuba, just 90 miles from the U.S. shoreline. A warhead launch from Cuba could have deposited a nuclear bomb on Washington, D.C. within 5 minutes.

Needless to say, the stakes were high.

In his October 22, 1962, national television address, Kennedy informed Americans about the presence of the missiles, announced a naval blockade surrounding Cuba, and let the world know the U.S. would use military force if the missiles were not removed.

What the American people didn’t know, getting to the naval blockade decision was not an easy one for Kennedy and there was tremendous pressure from the Pentagon and other ‘hawks’ in his administration to invade Cuba from the start.

With the dynamics behind how the crisis was resolved still being debated to this day by historians and academics, Khrushchev offered to remove the Cuban missiles in exchange for the U.S. agreeing never to invade Cuba and to also remove U.S. missiles from Turkey.

Crisis averted.

The Cuban Missile Crisis remains one of the most discussed and analyzed foreign policy crises ever; and, what the U.S. and Soviet Union (now Russia) learned from the October 1962 events has, arguably, kept us from getting that close to a nuclear war ever again.

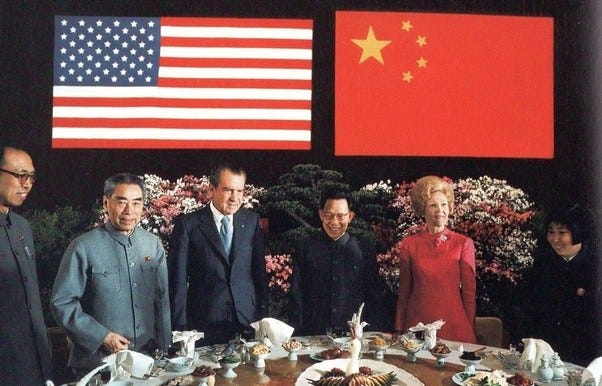

2. Nixon visits China (1973)

You know something is historically iconic when it can used as a referential device for other, unrelated events. ‘Only Nixon could go to China,’ is one of the common refrains, often used to explain why some major policy breakthroughs can only happen if previously strong opponents of the policy take up its cause. “Only Ronald Reagan could have pushed a national health care system through Congress,” was a frequent lament of a former colleague of mine. And, so on and so forth.

It is true, President Richard Nixon was a staunch anti-communist. It is also likely if a Democratic president had opened relations with Communist China, Nixon would have been its fiercest critic.

But politics has a funny way of turning preachers into sinners and soldiers into poets.

Nixon arrived in China on February 21, 1972, the Watergate break in four months later was still just a glint in his eye. At that time Nixon stepped off Air Force One into the cold air of Beijing, his administration was struggling with a war in Vietnam that looked increasingly like the South Vietnamese regime would not survive. Nixon knew the Vietnam War was no longer about containing communism’s expansion, but containing the damage to U.S. prestige around the world.

Yet, in February 1972, Nixon was never more confident in his ability to change the course of history. He was going to bring about an honorable peace in Vietnam, and further limit the Soviet’s ambitions by opening U.S. relations with the communist Chinese, Realpolitik‘s version of a Phil Niekro knuckleball.

It was diplomatic brilliance, and it worked, more in the long-term than in the short-term, however.

One of President Harry Truman’s most vocal critics at the time for losing China to the communists in 1949, Nixon thought he was ideal to fix Harry’s mistake. But, more strategically, Nixon and his National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, saw an opportunity to drive a small, but significant, wedge between the China and the Soviets, who were having minor border war skirmishes in the late 1960s. Nixon and Kissinger even thought a U.S.-China relations thaw would make the Soviets more amenable to U.S. interests.

China’s interests in the ‘thaw’ were even more complex, as the country was still in the middle of its brutal Cultural Revolution in which millions of Chinese intellectuals, leaders, and common citizens were persecuted for ‘bourgeois’ beliefs and activities. The Chinese economy was a mess and there was no better or quicker fix for a mess like that than American investment and trade.

In reality, Nixon’s trip to China was more symbolic than productive. But it did open the door to a symbiotic economic relationship that would eventually dominate the world economy forty years later.

The U.S.-China relationship is not as close as U.S.-European relations, and as we’ve seen with China’s growing military assertiveness in the South China Sea, disagreements are no longer restricted to economic issues. China is going to be a world superpower soon (if it isn’t already). Nixon’s trip to China in 1972, while not necessarily changing the inevitability or timing of China’s rise, it marks a significant point in history where the U.S., the leading economic and military power at the time, was preparing to welcome the Chinese back into a leadership role on the world stage.

Nixon will not be remembered as a great U.S. president, but by extending a hand of friendship to China, he showed a level of foresight quite rare among presidents.

1. Reagan and G. H. W. Bush manage the demise of the Soviet Union (1980s)

No single post-WWII conflict dominated American foreign policy as did theCold War with the Soviet Union. Our containment policy towards Soviet communism led directly to our involvement in Vietnam and underscored our country’s efforts to secure Middle East energy supplies for the West and our allies. In fact, many of the significant international crises involving the U.S. after World War II involved, directly or indirectly, the Cold War conflict: the Cuban Missile Crisis (1961), the Berlin Airlift (1948–49), and the Suez Crisis (1956–57). The Cuban Missile Crisis and the Suez Crisis, in particular, brought the two superpowers closer to a nuclear war than perhaps at any other time in the post-WWII world.

The arms race between the Soviet Union and the U.S. was the most costly military expansion in world history. The cost of the U.S. nuclear arsenal alone between 1940 and 1996 was estimated by the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI)to be around $5.8 trillion (in inflated-adjusted 1996 dollars), which was 31 percent of all defense expenditures during that period ($18.7).

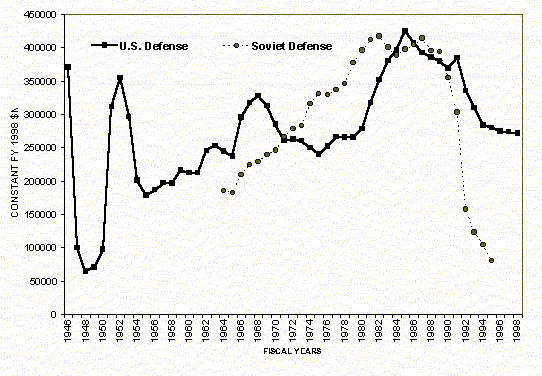

The Cold War was expensive. So costly, in fact, some believed the break-up of the Soviet Union was inevitable. But many experts also dispute attributing the Soviet Union’s demise to the Ronald Reagan-era military buildup. As the graph below shows regarding U.S. and Soviet Union defense spending between 1964 and 1998, Soviet defense spending had been increasing on a consistent basis long before the first Reagan defense budgets.

In disputing the contention that Reagan’s defense build-up accelerated the Soviet Union’s decline, Richard Ned Lebow and Janice Gross Stein wrote in The Atlantic in 1994:

“The Soviet Union’s defense spending did not rise or fall in response to American military expenditures. Revised estimates by the Central Intelligence Agency indicate that Soviet expenditures on defense remained more or less constant throughout the 1980s. Neither the military buildup under Jimmy Carter and Reagan nor SDI had any real impact on gross spending levels in the USSR. At most SDI shifted the marginal allocation of defense rubles as some funds were allotted for developing countermeasures to ballistic defense.

If American defense spending had bankrupted the Soviet economy, forcing an end to the Cold War, Soviet defense spending should have declined as East-West relations improved. CIA estimates show that it remained relatively constant as a proportion of the Soviet gross national product during the 1980s, including Gorbachev’s first four years in office. Soviet defense spending was not reduced until 1989 and did not decline nearly as rapidly as the overall economy.”

Instead, Lebow and Stein, like many experts in this area, considered the proximal cause of the Soviet Union’s demise to lie in the ill-conceived perestroika reforms initiated by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in the 1980s, coupled with the structural problems inherent in the Soviet economic system. If anything, the Reagan defense budgets delayed the Soviet Union’s demise.

Nonetheless, Reagan and his successor, George H. W. Bush, did something perhaps more important than bringing down the Soviet Union. They managed the Soviet decline, regardless of its many causes, and ensured that the new world order emerging from the end of the Cold War would be stable and prosperous.

So much could have gone wrong. From the time when the Berlin Wall came down on December 9, 1989 to December 26, 1991, the complex task of disentangling a Gordian knot of Soviet relationships around the world fell into the George H. W. Bush’s lap.

At the time of the Soviet collapse, the country had about 39,000 nuclear weapons and about 1.5 million kilograms of plutonium and highly enriched uranium, according to Stanford engineering professor Siegfried Hecker, who helped the former Soviet Union secure its nuclear arsenal at a time when many feared ‘loose nukes’ would get into the hands of the wrong people.

In his book, Doomed to Cooperate: How American and Russian scientists joined forces to avert some of the greatest post-Cold War nuclear dangers, Hecker argues that it was the intense cooperation between U.S. and Russian scientists, at the behest of their governments, that prevented what could have been a post-Cold War nuclear catastrophe.

And the cooperation between U.S. and former Soviet Union scientists and senior military personnel was, itself, built upon a positive relationship Ronald Reagan (and then George H. W. Bush) had built with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and other senior Soviet leaders.

It is not an exaggeration to suggest Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush made the world safer, faster than at any other time in U.S. history.

- K.R.K.