By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; December 19, 2018)

With the U.S. Senate recently voting to end U.S. assistance in the Saudi-UAE-led war in Yemen, the symbolic gesture may represent a genuine turning point in the three-and-a-half year conflict.

…or maybe just more false hope.

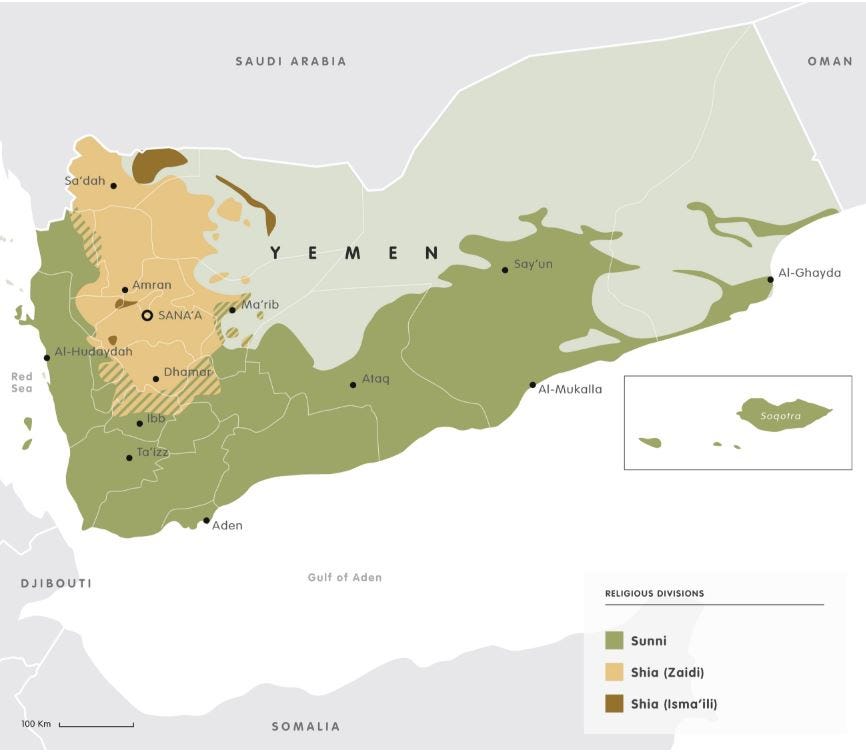

The Yemen civil war, in which no resolution is in sight, is generally portrayed as a conflict between the Houthi militia in western Yemen, a movement affiliated with the Zaidi sect of Shia Islam, and forces allied with Houthi-deposed Yemen President Rabbuh Mansur Hadi, a Sunni Muslim re-elected president in 2012 in a contest where he ran unopposed and received 100 percent of the popular vote.

Figure 1. Religious Map of Yemen

Layered within Yemen’s complex domestic situation, however, is a proxy war between Saudi-UAE-led forces and Iran, who backs the Houthis, though their level of support is disputed. But even this proxy war is itself embedded within a larger regional contest fueled by a U.S.-Israel-Saudi-led obsession with containing Iran’s growing (but limited) influence in the Middle East. The Israeli’s have a palpable and legitimate concern with Iran’s potential to control a continuous land-based supply route between Tehran and the potent and highly-trained Hizballah forces in southern Lebanon. The long-term posture of the U.S. occupation of Syria’s eastern provinces is, in fact, largely predicated on preventing this from becoming a reality.

From the Iranian perspective, their involvement in Syria in supporting the Bashar al-Assad regime, is a much higher priority than Yemen.

“Iran has an obtainable objective in Syria: protecting one of its few allies in the Arab world,” says Dr Michael O’Hanlon, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “Its goals in Yemen are far less defined.”

“Although both Syria and Yemen have been within the geopolitical radar of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) for at least the last decade, the former is much more important geostrategically as it constitutes a bridge to Hizballah and the Mediterranean,” says Dr Ali Fathollah-Nejad, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Doha Center. “Iran’s Yemen activities are primarily geared towards bogging down its regional rival Saudi Arabia.”

As such, the atrocities being perpetrated against the Yemenis are predominately owned by the Saudi-led coalition forces, which is why American and British complicity is so problematic.

The civilian toll in Yemen (as best we can discern)

Any attempt to measure civilian deaths and casualties resulting from the civil war is fraught with difficult and likely to be imperfect. Nonetheless, growing international attention to the conflict is bringing with it conscientious efforts to measure its social costs.

An effort to measure Yemeni civilian deaths by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), an independent group formerly associated with the University of Sussex (UK), is one such example.

“We estimate the number killed to be 56,000 civilians and combatants between January 2016 and October 2018,” says Andrea Carboni, an ACLED researcher who focuses on Yemen. ACLED further estimates that 2,000 Yemeni civilians are now dying each month largely due to malnutrition and diseases such as cholera.

The ACLED estimate of 56,000 deaths is significantly higher than previous estimates that have typically assessed the civilian death toll in Yemen to be around 10,000.

“One reason Saudi Arabia and its allies are able to avoid a public outcry over their intervention in the war in Yemen, is that the number of people killed in the fighting has been vastly understated,” writes long-time Middle East correspondent Patrick Cockburn. “The figure is regularly reported as 10,000 dead in three-and-a-half years, a mysteriously low figure given the ferocity of the conflict.”

Why 10,000 deaths wouldn’t be sufficient to inspire a public outcry is unclear, but regardless of the precise number, what is clear is the consistent attention now being placed on the Yemen civil war by the European media. [Sadly, the U.S. media can’t seem to break away long enough from their mostly dishonest Trump-Russia collusion narrative to actually cover the Yemen conflict with any depth.]

And as this light is being directed towards Yemen, more attention is being focused on the genuine possibility that war crimes have been committed by the Saudi-UAE-US-UK coalition.

What is a war crime?

The body of statutes often used to define a war crime are the Geneva Conventions, the Hague Convention on land warfare of 1907 (concerning the Laws and Customs of War), and the 1998 International Criminal Court Statute.

Article 23 of the 1907 Hague Convention expressly states that it is forbidden:

(a) To employ poison or poisoned weapons;

(b) To kill or wound treacherously individuals belonging to the hostile nation or army;

(c) To kill or wound an enemy who, having laid down his arms, or having no longer means of defence, has surrendered at discretion;

(d) To declare that no quarter will be given;

(e) To employ arms, projectiles, or material calculated to cause unnecessary suffering;

(f) To make improper use of a flag of truce, of the national flag or of the military insignia and uniform of the enemy, as well as the distinctive badges of the Geneva Convention;

(g) To destroy or seize the enemy’s property, unless such destruction or seizure be imperatively demanded by the necessities of war;

(h) To declare abolished, suspended, or inadmissible in a court of law the rights and actions of the nationals of the hostile party. A belligerent is likewise forbidden to compel the nationals of the hostile party to take part in the operations of war directed against their own country, even if they were in the belligerent’s service before the commencement of the war.

Similarly, Article 147 of the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention defines war crimes as:

“Wilful killing, torture or inhuman treatment, including biological experiments, wilfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health, unlawful deportation or transfer or unlawful confinement of a protected person, compelling a protected person to serve in the forces of a hostile Power, or wilfully depriving a protected person of the rights of fair and regular trial prescribed in the present Convention, taking of hostages and extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly.”

Finally, in creating the International Criminal Court (ICC), the 1998 International Criminal Court (Rome) Statute formally established the ICC’s functions, jurisdiction and structure. Specifically, it empowered the ICC to investigate and prosecute four international crimes: genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crimes of aggression.

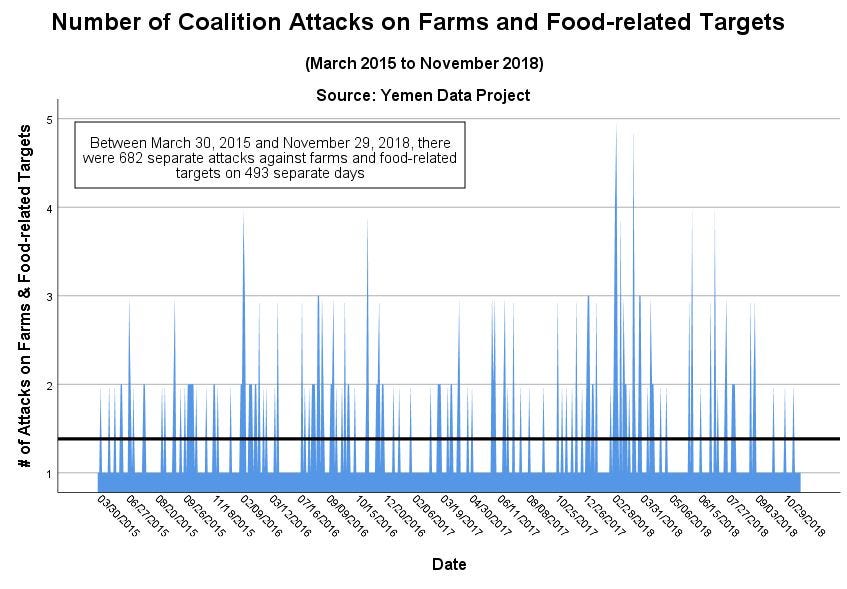

The “extensive destruction…of property, not justified by military necessity” constitutes a war crime according to the Geneva Conventions and Rome Statute and, in the case of Yemen, this would seem to describe the coalition’s attacks on Yemen, particularly its water and food infrastructure (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of Daily Coalition Attacks on Farms and Food-related Targets (March 2015 to November 2018)

The Laws and Customs of War allow for states to attack an enemy combatant’s economic and military infrastructure in order to degrade its military effectiveness. But the primary consequence of destroying a nation’s food production and distribution system is famine among the civilian population.

That is a war crime.

In an independent report submitted in October 2018 to the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, London School of Economics and Political Science Professor Emeritus Martha Mundy, the report’s author, offered this observation:

“If one places the damage to the resources of food producers (farmers, herders, and fishers) alongside the targeting of food processing, storage and transport in urban areas and the wider economic war, there is strong evidence that Coalition strategy has aimed to destroy food production and distribution in the areas under the control of Sanaa,” wrote Mundy.

“Deliberate destruction of family farming and artisanal fishing is a war crime,” she concluded, citing the 1977 Protocol I additional to the Geneva Conventions, which, through International Humanitarian Law, protects objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population.

In building the report’s case, Mundy relied heavily on data from the Yemen Data Project (YDP), which has been tracking coalition military strikes and incidents in Yemen since 2016.

Along with the ACLED, the evidence collected through the YDP’s systematic and comprehensive data collection may prove indispensable should the Saudis and its coalition partners be investigated for war crimes in the future.

The Yemen Data Project

The Yemen Data Project (YDP) is an independent, non-profit data collection project aimed at increasing the transparency over the conduct of the Yemen civil war.

The YDP collects military event data through open sources that are “cross-referenced with local and international news agencies and media reports; social media accounts, including Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and other video footage, and WhatsApp; reports from international and national NGOs; official records from local authorities; and reports by international human rights groups.” When independent reporting is unavailable, the data has been cross referenced with sources from opposing sides to the conflict as to ensure the reporting is as accurate and impartial as possible.

In YDP’s words, their data represents the “best current current understanding of incidents” in Yemen.

Characteristics of coalition attacks on Yemen

Many years ago I taught an introductory international politics class at The University of Iowa and one of its obligatory class segments covered the “laws of war.” As I always allocated the last 15 minutes of the class to an open discussion about the lecture topic of the day, this particular segment elicited strong opinions among students. Even the most marginal students seemed to have an opinion about how wars the acceptable rules of war.

From class to class, variants on these questions would inevitably emerge:

“How is that chemical weapons are unacceptable, but dropping atomic bombs (on Hiroshima and Nagasaki) is OK?”

“If you are at war with another country, aren’t you also at war with its citizens?”

“How can there be rules for war? It’s war!”

Unlike today’s educational environment, my classes in the early 90s made no attempt to suppress or censor ideas or opinions. The class debates were lively, contentious and open-ended, never ending in a broad consensus on what constitutes a ‘war crime’ or acceptable laws for war.

Differences of opinion were exciting in the day.

At some point during the class discussion, I would offer these quotes from U.S. Air Force General Curtis LeMay, best known for his role in planning and executing a massive bombing campaign against cities in Japan during World War II, in addition to his tenure as Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force from 1961 to 1965:

“There are no innocent civilians. It is their government and you are fighting a people, you are not trying to fight an armed force anymore. So it doesn’t bother me so much to be killing the so-called innocent bystanders.”

“Killing Japanese didn’t bother me very much at that time… I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal…. Every soldier thinks something of the moral aspects of what he is doing. But all war is immoral and if you let that bother you, you’re not a good soldier.”

In no way did I endorse General LeMay’s views on civilians and warfare (in fact, I despise the man), but I shared the quotes as I felt he conveyed the fundamental argument (still made today) as to why civilians are legitimate targets in war.

Like it or not, ‘war crimes’ often depend on the eye of the beholder.

Had the U.S. lost World War II, the Allies’ fire bombing of Hamburg, Dresden and Tokyo would have defined ‘war crimes’ for generations. As it turned out, such attacks, at least from the Allies’ perspective, were just the realities of war.

Why should the war in Yemen require different rules?

Because human thinking has evolved since World War II, that’s why.

Two hypotheses about civilian targeting in the Yemen civil war

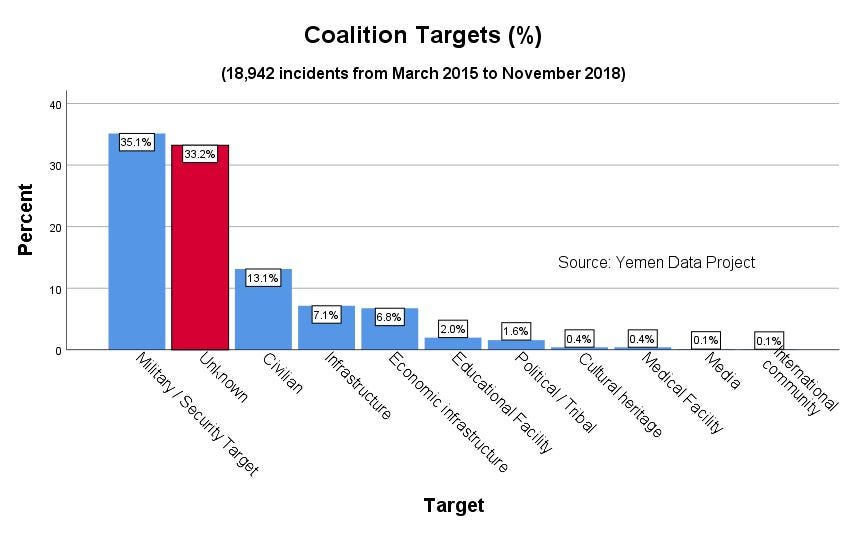

With over 18,900 military incidents between March 2015 and November 2018 in their database, the YDP offers the best open-source information available on the Yemen conflict. Along with the date and the time of day (daypart) of the incident, the YDP database also includes location and summary target information.

In analyzing this data, while I use the YDP’s data to reference the ‘target,’ it is dangerous to assume the intended ‘target’ for each incident. What we can assume, however, is that anyone on the receiving end of a coalition bombing attack felt like a ‘target’ and so that is how I define the term in the following analyses.

The guiding purpose in this analysis, therefore, is to describe the anti-Houthi coalition’s ‘targeting’ as part of the process in determining whether civilians were systematically targeted.

The YDP dataset alone, however, cannot discern the targeting intent of the coalition’s military leadership, but it offers one of the best open-source insights into this question: How would we know if civilians were systematically targeted by the coalition?

Short of possessing internal coalition communications and targeting process memos, we are forced to discern targeting intent through identifying patterns within the attacks. And to do that, we must start with hypotheses regarding the patterns we’d expect to see in the YDP data if the targeting of civilians was premeditated and systematic.

Let us start with a hypothesis, if true, would go a long way in exonerating the coalition from charges of targeting civilians.

H1: If coalition attacks against Yemeni civilians were incidental, their occurrence within the YDP data should be patternless, random events that otherwise track closely to the coalition’s non-civilian attack patterns.

And even if this hypothesis (H1) is rejected by the data and we find a pattern within civilian attacks, we may still find evidence that the coalition, while targeting civilians areas, systematically made an effort to avoid excessive civilian casualties.

Our second hypothesis addresses how the data might reflect that reality.

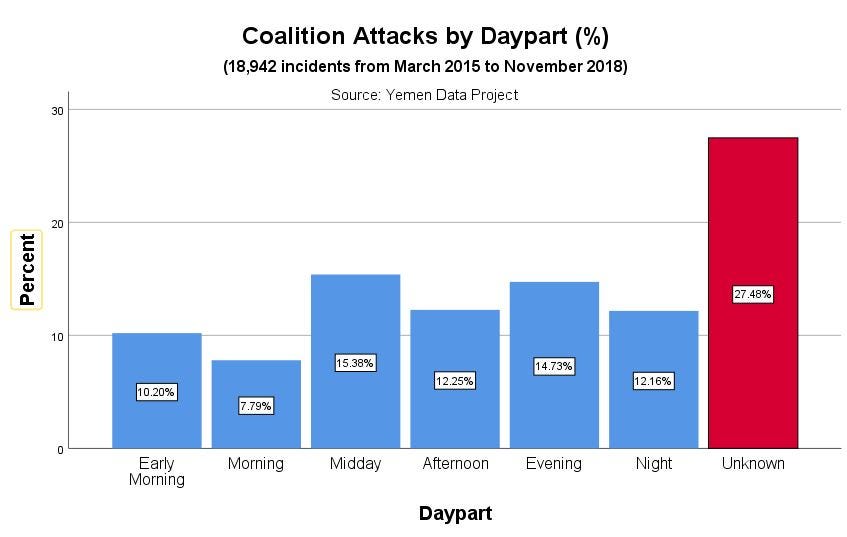

H2: If, in targeting civilian areas in pursuit of military objectives, the coalition attempted to minimize civilian casualties, we should expect coalition targeting of civilian areas to be concentrated on dayparts when civilians tend to be away from their homes.

Specifically, civilians tend to be at home in the evening, nighttime, and early morning hours and away from home in the morning, midday and afternoon hours. Did the coalition systematically try to avoid hitting civilian areas during dayparts when people tend to be home?

Let’s to go the data and see what we find…

Characteristics of coalition attacks on Yemen

Before testing our two hypothesis, let us describe the YDP data more generally.

Figure 3 (below) breaks out the targets of every coalition attack since March 2015 and finds that 35 percent of the coalition’s targets since March 2015 were military or security related, followed by ‘unknown’ targets (33%) and civilian targets (13%). Infrastructure targets (transportation and economic, etc.) accounted for 14 percent of all coalition targets.

Figure 3. Coalition Targets

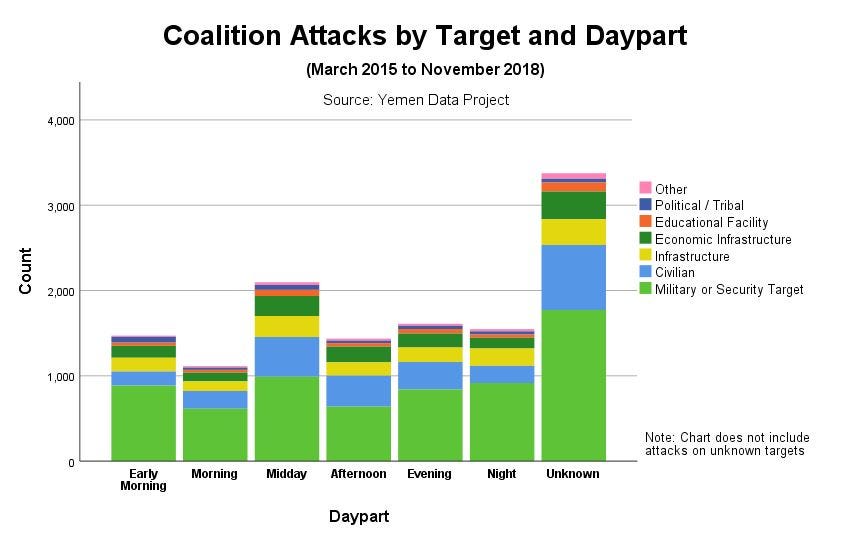

Military and civilians targets were the primary focus of coalition attacks against Houthi forces between March 2015 and November 2018. And as seen in Figure 4 (below), the coalition attacks tended to occur at all parts of the day, though most occurred between midday and the early evening hours.

Figure 4. Coalition Attacks by Daypart

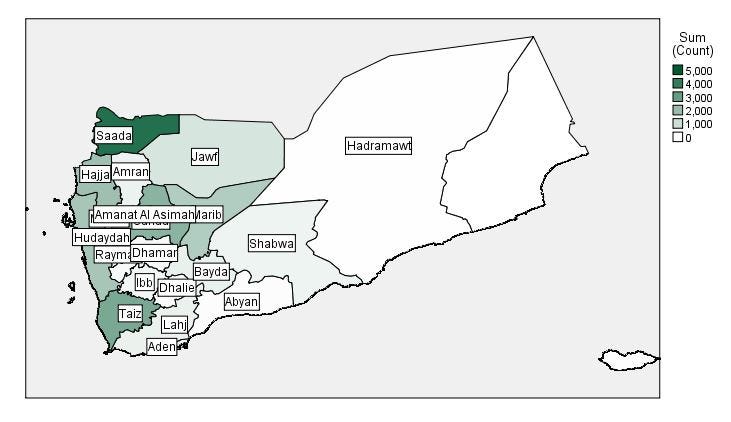

A mapping of coalition attacks (Figure 5) closely correlates with the tribal and religious clusters within Yemen, with the most intense bombing experienced in areas populated by the Zaidi (Shia) and Isma’ili (Shia) tribes in the Saada governorate.

Figure 5. Coalition Attacks by Governorate (March 2015 to November 2018)

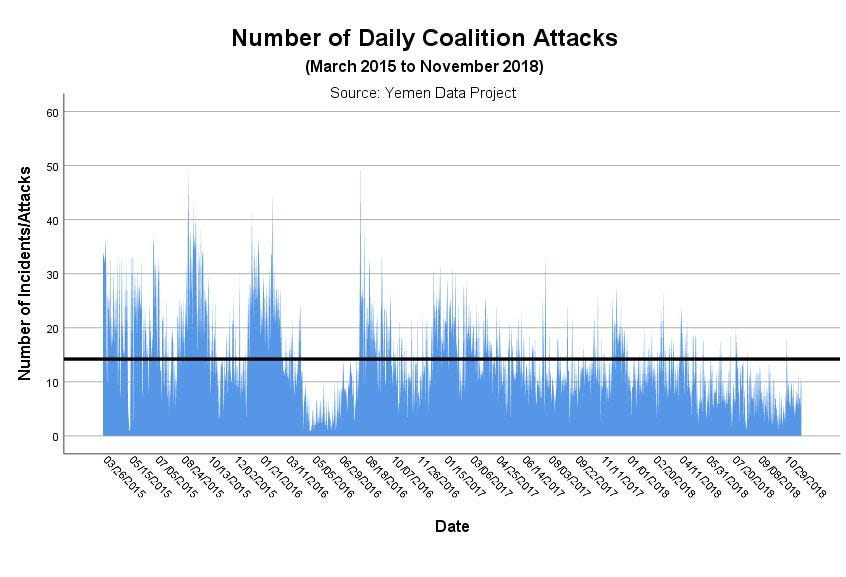

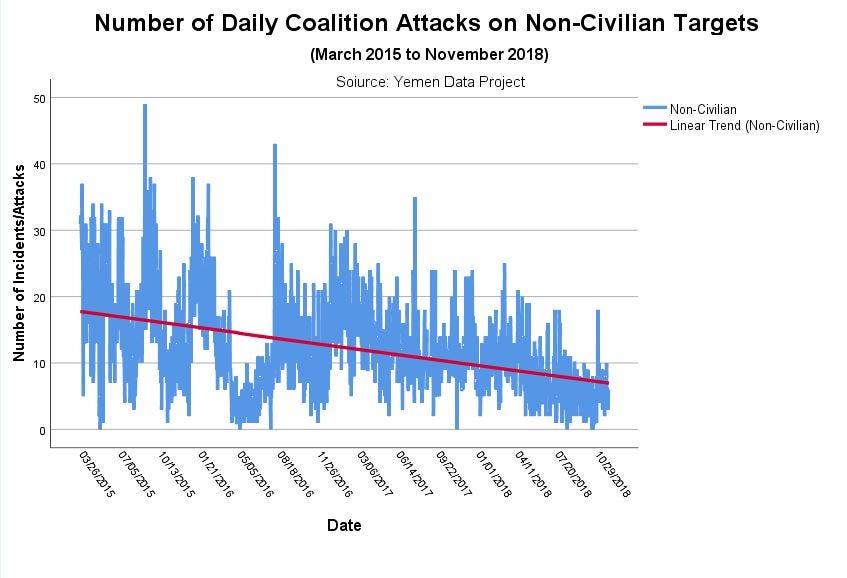

The distribution of coalition attacks over time highlights two other major features of the Yemen civil war (see Figure 6). First, the number of daily attacks have generally decreased over time, going from about 20 per day between March 2015 and March 2017 to about 10 per day after March 2017. The second feature is a more dramatic decrease in attacks during a ceasefire period in May 2016.

Figure 6. Number of Daily Coalition Attacks (March 2015 to November 2018)

Besides the modest decline in the coalition’s daily attack tempo over the three-and-a-half years of the civil war, there are no other obvious patterns (e.g., seasonal) within the YDP data. However, the task here is to discerns patterns (or lack thereof) within the coalition’s attacks on civilian targets.

To do that, let us look closer at the YDP’s civilian target data.

Are Yemeni civilians being targeted by the coalition?

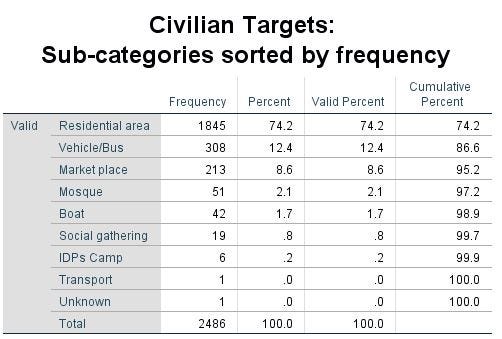

At this point, a brief understanding of what was included (and not included) in the YDP’s definition of a civilian target is helpful. Almost 75 percent of civilian targets in the YDP database were residential areas, followed by vehicles/buses (12%) and market places (9%). There were even 51 attacks on mosques, representing two percent of all attacks on civilian targets.

Figure 7. Sub-categories of Civilian Targets

There are other civilian targets such as schools and medical facilities which YDP breaks out separately; though, those targets represent less than three percent of all coalition targets (see Figure 3 above).

My sub judice presumption is that, if civilian attacks are not the conscious result of military targeting, then their occurrences over time (‘accidents’ if you will) should be distributed randomly.

That is essentially the argument the Saudis have made when confronted by the international community about civilian casualties in the Yemen conflict.

In October 2018, after the Saudis had killed over 40 school children during an airstrike in August, Saudi Defense Minister Osaiker Alotaibi told an international investigatory panel that the Saudi-led alliance had a list of 64,000 civilian targets in Yemen that they would never attack, including schools and hospitals. Alotaibi stated further to the panel that previous civilian casualties were the result of “unintentional mistakes” and were not premeditated.

But in his testimony to the panel, Alotaibi also said the Houthis were putting civilians — including children — in harm’s way by using schools and hospitals as “refuges” for Houthi fighters.

Houthi representatives strongly deny Alotaibi’s accusation.

Regardless, if the Saudi ‘sloppy targeting’ defense is truthful, we should see evidence of it in the YDP data. Specifically, we should find the number of civilian attacks from day-to-day to be strongly correlated with the number of non-civilian attacks (primarily military/security-related targets); and, where they are not related, the variation in civilian attacks should be randomly distributed over time. Noise, in other words.

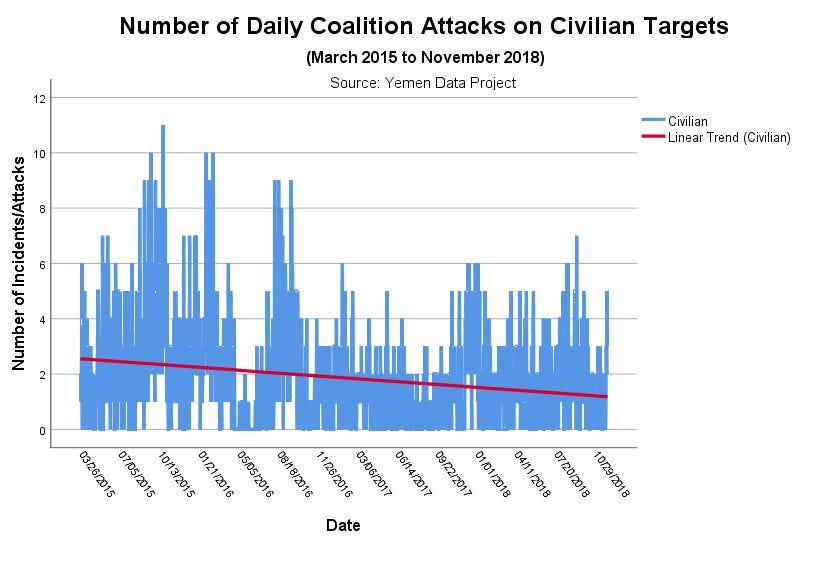

Figure 8 (below) plots civilian and non-civilian attacks over time, as well as the trend for each. Clearly, civilian and non-civilian attacks are correlated. Notice in both charts the three spikes in attacks between October 2015 and August 2016. Also, both show a similar downward trend in daily frequency.

On the surface, therefore, there is evidence to support the Saudi’s ‘sloppy targeting’ defense.

Figure 8. Number of Daily Coalition Attacks on Civilian and Non-Civilian Targets (March 2015 to November 2018)

But surface looks can be deceiving, and a more formal analysis was done to see if civilian targeting was, in fact, merely collateral damage resulting from an otherwise legitimate military targeting process.

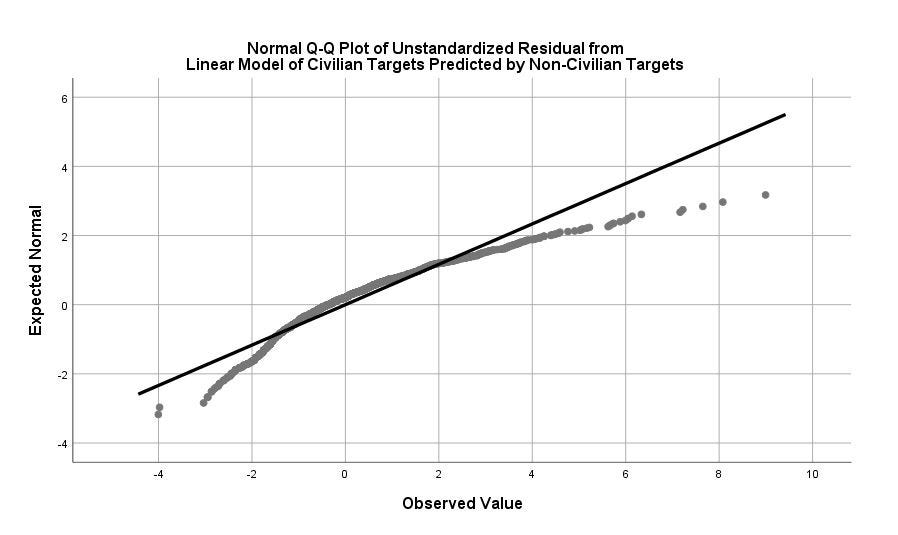

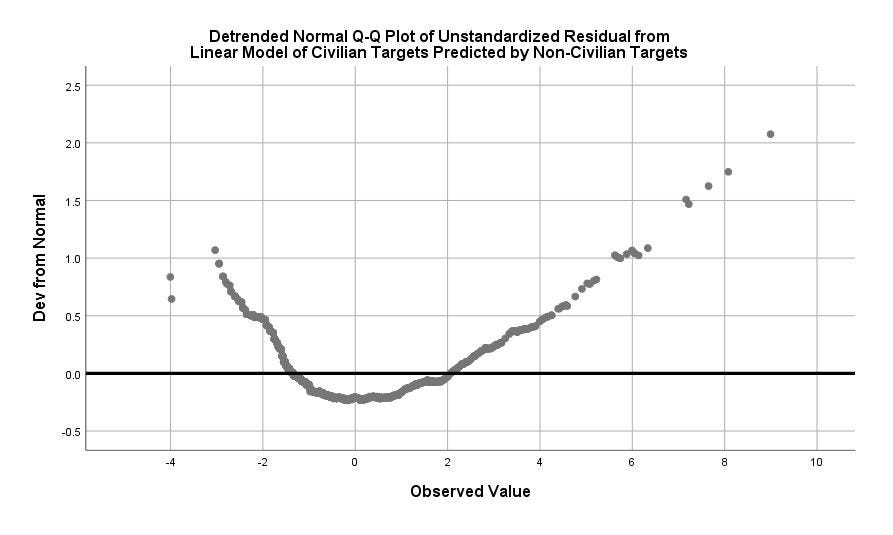

To do that, I first regressed the number of civilian target events on the number of non-civilian target events and used the residual from that equation to represent variation in civilian target events unrelated to non-civilian target events. Subsequently, I conducted a residual analysis to determine if the model residuals were normally-distributed, random noise.

Figure 9 (below) shows that the variation in the number of civilian attacks not explained by non-civilian attacks (i.e., the residual) is not a normal, randomly distributed variable.* More importantly, we can conclude that the day-to-day variation in coalition attacks on civilian targets cannot be explained by the military necessities of non-civilian targeting.

*The Shapiro-Wilk test of normality was highly significant, indicating the data was not normally distributed.

Figure 9. Normal Q-Q Plot and Detrended Q-Q Plot of Unstandardized Residual from a Linear Model of Number of Civilian Targets Regressed on Number of Non-Civilian Targets

We have rejected our first hypothesis (H1) that civilian attacks by the coalition were merely the product of a legitimate military targeting process, but is there any evidence the coalition tried to minimize civilian casualties when they targeted civilian areas?

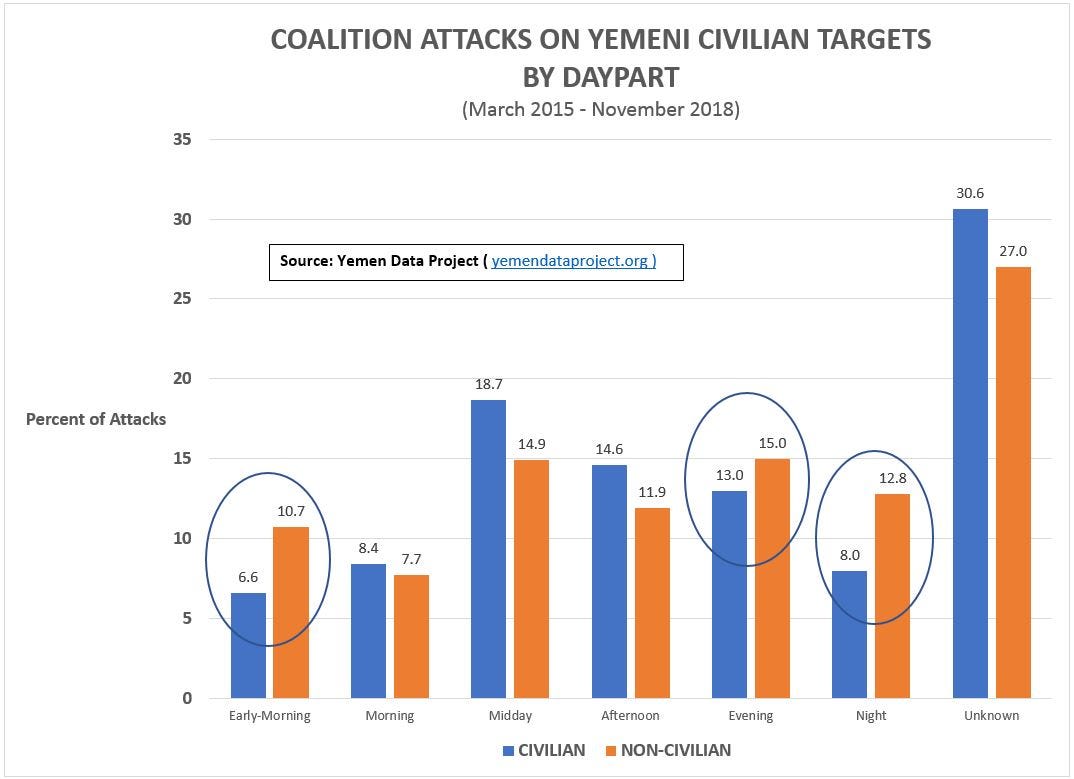

To answer that question, I looked at coalition attacks on civilian and non-civilian targets by daypart (early morning, morning, midday, afternoon, evening, night). It is reasonable to presume that any attempt by the coalition to minimize civilian casualties would involving striking civilian targets (typically residential areas) during a time of day when civilians would not be home: namely, the midday and afternoon dayparts.

In Figures 10 and 11 (below) we see evidence of exactly that.

Where non-civilian attacks have tended to occur in the early morning (11%), evening (15%) and night (13%) dayparts, civilian attacks have tended to occur at midday (19%) and in the afternoon (15%). This is consistent with the Alotaibi claim that the coalition has in place procedures to avoid unnecessary civilian casualties.

Still, approximately 28 percent of coalition attacks on civilian targets — most often residential areas — have occurred at times when people tend to be home (evening, night, early morning) — which translates into 688 separate and verifiable incidents (about one incident every other day) that the coalition attacked a civilian target at time when people will tend to be home.

Figure 10. Coalition Attacks on Yemeni Civilian vs. Non-Civilian Targets (by Daypart)

Figure 11 offers further evidence that the coalition may have preferred the midday and afternoon dayparts for attacks on civilian targets. Where civilian targets constitute around 13 percent of all attacks, they represent percent of between 22 and 25 percent of attacks in the midday and afternoon. This suggests the coalition may make an effort to minimize civilian casualties by conducing their attacks on targets in civilian areas at times when people tend to be at work, school or away from home.

This finding may not fully exonerate the Saudi-led coalition for possible war crimes committed against Yemeni civilians, but should the coalition partners face an ICC inquiry, it may offer at least partial exculpatory evidence.

Figure 11. Coalition Attacks by Target and Daypart

Final thoughts and next steps

What is most striking in the YDP data is the unrelenting consistency of the coalition’s operational tempo against Yemen. The bombers take very few days off.

Apart from the brief ceasefire period in May 2016, the coalition has unleashed almost 19,000 separate attacks on Yemen within less than four years (1,333 days). That works out to between 10 to 20 attacks every day.

And to what end? There is no evidence that the Houthis are going to relinquish power in western Yemen, and while there has been a slight decline in the coalition’s operational tempo since the Saudi’s assassination of Jamal Khashoggi, the coalition’s attacks show no sign of ending soon either. And as long as the conflict continues, the work of the YDP and other similar independent groups are going to be critical for the foreseeable future.

And who will be paying attention to this unfolding tragedy that the UN calls the ‘world’s worst humanitarian disaster?

With all due respect to the U.S. Senate vote condemning the Saudi’s actions in Yemen, don’t expect much more from the America’s greatest deliberative body. There are few Capitol Hill advocates for Yemen, which controls no major oil or gas reserves and is home to not one oligarch likely to attend Davos next year. Taken together, this all but guarantees Yemen will not stay on the front burner of Senate business.

Even the world’s news media organizations have taken a ho-hum approach to covering the Yemen tragedy, as they have been far more more preoccupied with the conflict in Syria. The U.S. media, in particular, continues to show little interest in Yemen. In an analysis by media journalist Adam Johnson, it was found that between July 3, 2017 and July 3, 2018, MSNBC (the number one cable news network in that period) dedicated “zero segments to the US’s war in Yemen, but 455 segments to Stormy Daniels.”

That pretty much sums up American broadcast journalism today.

With that backdrop, this article represents the first in a series of data analyses I will be conducting on the YDP data. Additionally, I will be augmenting the YDP event data with other data sources (such the temporal-geographic distribution of cholera cases) to further investigate the impact the coalition’s attacks have had on the Yemen civilian population.

Only with transparency will there be any chance to hold Saudi Arabia, UAE, and their coalition partners accountable for their actions in Yemen.

-K.R.K.