By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; June 14, 2019)

Has the Yemen Civil War entered into its final stages or is it about to get worse?

The long-term decline in Saudi-UAE air attacks in Yemen suggest the former, but recent Houthi rebel missile attacks on Saudi Arabia’s Abha airport and the subsequent promise by the Saudi-UAE coalition to retaliate would indicate otherwise.

As I write, the Saudi’s are claiming this morning (June 14) to have shot down five Houthi-fired unmanned drones near the same airport.

Shadowing this conflict are the increasing tensions between the U.S. and Iran, who backs the Houthi rebels in Yemen, punctuated in the past few days by mine attacks on Persian Gulf oil tankers, which the U.S. blames on Iran.

Until this week, the trend in Yemen was looking positive

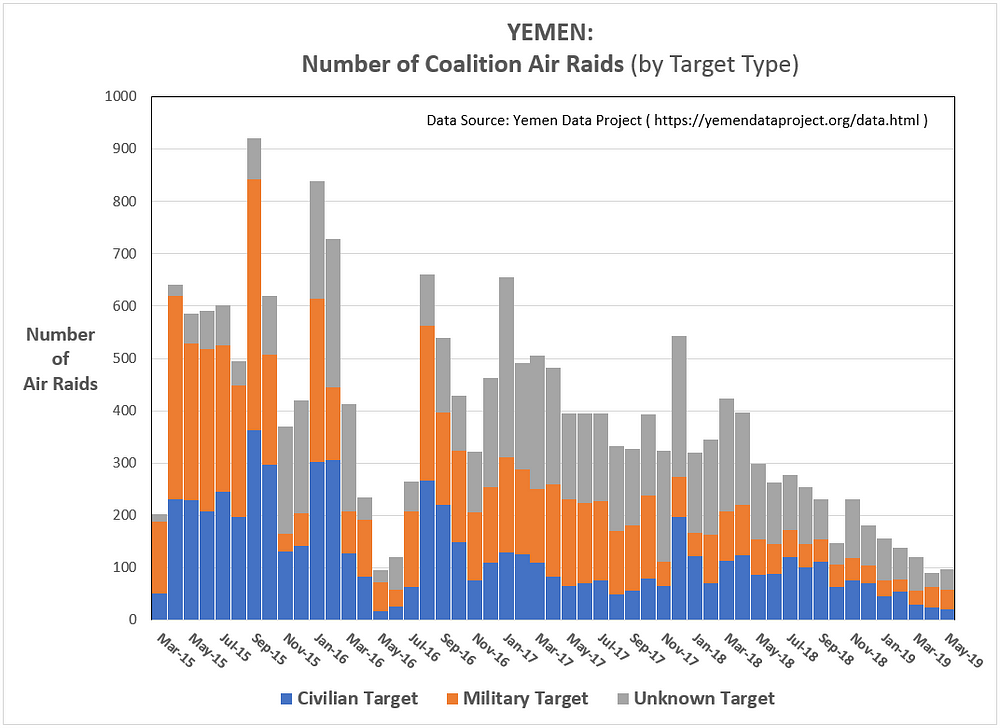

These regional setbacks notwithstanding, the long-term trends in Saudi-UAE coalition air raids on Houthi-held areas of western Yemen have been showing a distinct downward trend (see Figures 1 and 2). In April and May, the coalition launched its fewest air raids since May 2016, a period in which a cease fire was in place. Similarly, the number of civilian deaths caused by the coalition air raids and the lethality of these raids are near three-year lows.

Figure 1: Saudi-UAE Coalition Air Raids on Yemen (March 2015 to May 2019)

Figure 2: Deaths caused by Saudi-UAE Coalition Air Raids on Yemen (March 2015 to May 2019)

Given the Houthis have relinquished little of the territory they seized at the start of the civil war in 2015, any resolution to the conflict, with the status on-the-ground as it is, will most likely favor the rebels.

Writing in Foreign Affairs last month in support of continued U.S. cooperation with the Saudi-UAE coalition, Michael Knights, Kenneth Pollack, and Barbara Walter acknowledged that the “the fighting will go on, and innocent Yemenis will continue to die until one side — most likely the Houthis — have won.”

Last December, the Houthi rebels and the Saudi-UAE coalition agreed to a limited ceasefire and withdrawal of forces from Red Sea port city of Hudaydah, a Red Sea port city where most humanitarian aid enters Yemen.

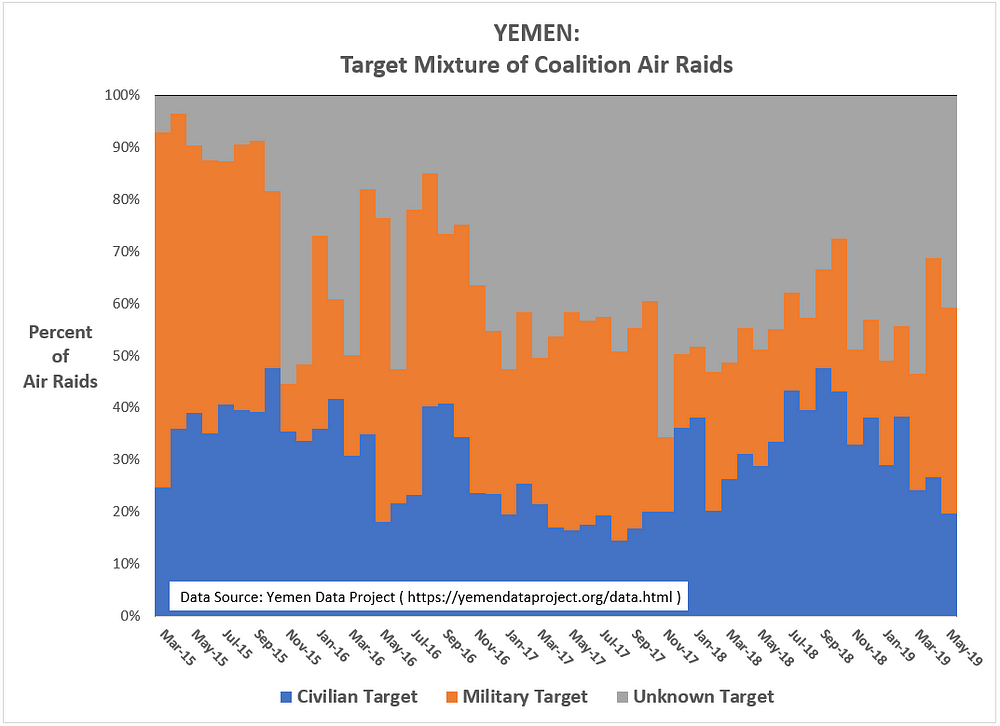

Still, the Saudi-UAE forces (with U.S. assistance) continue to attack civilian, non-military targets (see Figure 3). Since the war began, around one-quarter of all coalition air raids have targeted civilians. This level has been relatively constant, though it surged past 40 percent in the Summer of 2018 when coalition forces started a large offensive to retake Hudaydah. The coalition failed and, in the process, committed one of its worst atrocities yet when an air strike hit a bus in Dahyan, in Yemen’s Saada province, killing over 50 people, including dozens of children.

Figure 3: Target Mixture of Saudi-UAE Coalition Air Raids on Yemen (March 2015 to May 2019)

Can an escalation in the Yemen War be avoided?

With the probability of a hot war between the U.S. and Iran rising substantially since the U.S. exited the Iran nuclear deal and imposed new sanctions against Tehran, the prospects for a peaceful resolution in Yemen seem remote.

But there is cause for optimism. For one, the harsh economic realities now facing Iran will significantly constrain its ability to increase its military assistance to the Houthis. This week’s Houthi attacks on the Saudi airport may have been about sending a message to the Saudi-UAE coalition: With or without Iran’s help, the Houthis are not going away.

At the same time, the reality of a weaker Iran may push the Houthis to negotiate a resolution to the War in Yemen. The Houthis, who are Shia Muslims, represent the majority in northwestern Yemen, which is also where the capital, Sanaa, is located. [Approximately 45 percent of Yemen’s population is Shia, the remaining mostly Sunni Muslims]

When the Houthi rebels removed Saudi-aligned President Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi from power in Yemen in 2015, ostensibly over Hadi’s decision to raise fuel subsidies, the rebellion was more about Houthi resentment over the undemocratic means by which Hadi, a Sunni, was placed into power by the Saudis.

The 2011 Arab Spring led to a revolution in Yemen in which the people forced their long-time leader, Ali Abdullah Saleh, generally considered allied with the West, from power. Hadi’s subsequent rise with Saudi support, however, only heightened tensions.

But the ability of the Houthis to unify Yemen is no more credible than Hadi’s attempt. At some point, all sides will need to negotiate a new political consensus if Yemen is to become a unified nation again, according to one of Yemen’s most prominent activists. Speaking at forum in Doha, Qatar last November, Tawakkol Karman, a Yemeni journalist and 2011 Nobel Peace Prize winner, was optimistic about ending the war and humanitarian crisis in Yemen, but it will require an international effort, starting with the ending of arms shipments to Yemen by the Saudi-UAE coalition and Iran.

She described the 2011 Yemen revolution as dedicated to the rule of law, freedom and peaceful coexistence and that it was external forces (Saudi Arabia, UAE, Iran, etc.) that overturned the revolution’s initial positive results.

In contrast to most Western observers, Karman blames both the Saudi-UAE coalition and the Iranians for the humanitarian crisis in Yemen today. The United Nations estimates around 10 million people in Yemen suffer from malnutrition and inadequate access to clean water. Since the war started, an estimated 85,000 Yemeni children under the age of five have died, according to the aid organization Save the Children. Left unaddressed, the UN estimates the world’s worst humanitarian disaster today could witness over 14 million Yemenis at risk of starvation.

“Children are falling like the leaves of autumn under the bombardments of the Saudi-led coalition,” Karman told the Doha audience.

To stop this ongoing tragedy, Karman believes the Yemeni constitution drafted during the 2011 revolution is the place to start. In it, regional autonomy for groups like the Houthis would be established while still maintaining a national structure for preventing any dominate sectarian interest from subjugating other groups.

But for that process to have a chance, the weapons have to stop pouring into Yemen, according to Karman.

The events in the Persian Gulf this week do not inspire confidence that a reduction in arms entering Yemen is going to happen soon. More likely, the Houthis and Saudi-UAE coalition will become even more entrenched.

However, with the Trump administration incautiously blowing up the regional status quo, the futility of the Yemen War may become apparent to both sides. The Houthis are going to lose significant materiel support from the Iranians, while the Saudi-led Gulf States are going to be increasingly distracted by a potentially larger conflict with Iran.

Now may be the best time for both sides to come to the negotiating table and start the slow process of re-building the democratic institutions started in Yemen after the 2011 revolution.

We can hope.

- K.R.K.