By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; January 11, 2019)

[DATA ANALYZED IN THIS ESSAY ARE AVAILABLE HERE ===> QUARTERLY_TERRORISM_DATABASE_EXPORT]

A little over a week ago I caught up on some YouTube podcasts to which I subscribe. One of my favorite podcasts — along with The Jimmy Dore Show and the CrazyRussianHacker) — is MoFreedomFoundation, a channel (and website) started by author Robert Morris dedicated to current affairs, international politics and ‘pro-sanity propaganda.’

“We promise to do a better job covering these issues than any cable news channel” is the MoFreedomFoundation’s pledge.

Not hard to do, unfortunately.

The Hypothesis

Morris’ latest podcast — “Islamic Terrorism is Over” — was particularly interesting and inspired me to do a quick data analysis to see if I could confirm (at least tentatively) his central hypothesis:

Since 2014, as oil prices have declined, the financial sponsors of terrorism — oil-rich Gulf countries such as Saudi Arabia and UAE — have seen their cash reserves decline and have therefore had less to use for funding terrorist activities (e.g., ISIS).

Here is the MoFreedomFoundation podcast spelling out that hypothesis and the empirical data supporting it:

“Almost three years ago I predicted that due to falling oil prices radical Islamic terrorism would quickly start to fade away — and that is exactly what happened,” starts Morris. “It was always Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf states that funded all that death and destruction. Now that they have less spare money, everybody else gets less.”

As Morris points out, this is not a thesis heard too often in the mainstream news media. Why?

“Every media and government organization in the world profits from fear and they really don’t want to document the fact that one of the biggest justifications for their budgets is in the process of disappearing.”

In fairness, I have heard or read this argument a few times recently within the climate change activist community where a number of researchers and journalists are using the link between oil money and terrorism to justify a more rapid transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

Author Nathan Taft, from the Fuel Freedom Foundation, writes: “When you pay at the pump, your hard-earned cash isn’t just going to oil companies — it also fills the pockets of terrorists and hostile regimes that harbor dangerous ideologies.”

There you go. When you fill up the Volvo, you aren’t just preparing for a two-hour drive to Aunt Velma’s, you’re helping finance the car bomb industry — in case you need another good reason not to visit Aunt Velma.

When ISIS controlled meaningful amounts of territory, it also controlled oil and gas fields, where it was able to generate significant revenues for their activities.

But we know from leaked U.S. State Department documents from 2009 that Saudi Arabia was — and likely still is — the “world’s largest source of funds for Islamist militant groups such as the Afghan Taliban and Lashkar-e-Taiba.”

According to the report signed by then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, “Donors in Saudi Arabia constitute the most significant source of funding to Sunni terrorist groups worldwide.” The report also identifies Qatar, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) as other significant sources of terrorism funding.

Keep in mind, the Saudi incentive for much of its terrorism funding is in keeping Iran’s hands full. ISIS was causing Iran to bleed resources in order to keep afloat the Bashar al Assad regime, one of the few Iranian allies in the region. Likewise, ongoing Saudi support for Islamist militants in Yemen fighting Houthi (Shia) forces compels Iran to dedicate resources to that war than they might otherwise prefer to use elsewhere.

[There is actually little evidence that Iran has a major financial or military commitment in Yemen. At least, nothing compared to what Saudi Arabia and UAE are committing.]

Even as Saudi Arabia appears to be working to stop the flow of money to Islamic militants, the country openly finances the philosophical training ground for such militants through their support to a worldwide Wahhabi education system.

Saudi Arabia is both the arsonist and the firefighter.

The Data

So, the Morris podcast prompted me to pull together a couple of data sources to test the “Cheap Oil Stops Terrorism” (COST) hypothesis.

First, we need valid and reliable terrorism data.

While in the past I have used the Global Terrorism Database (GTD), compiled by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) at the University of Maryland, College Park, I was intrigued by Morris’ use of a database maintained by the anti-Islam website TheReligionOfPeace.com (TROP).

Morris describes the website well: “TheReligionOfPeace.com website claims to provide a comprehensive list of terror attacks across the world, (though) the vast majority of the incidents come from active war zones like Iraq Syria and Afghanistan.”

The website is “one of the most bigoted and anti-Islamic news sources you can find,” concludes Morris.

Yet, oddly enough, the TROP database strongly correlates with the terrorism death and incident counts in the GTD. Therefore, for this brief analytic exercise, I felt comfortable sticking with the TROP data.

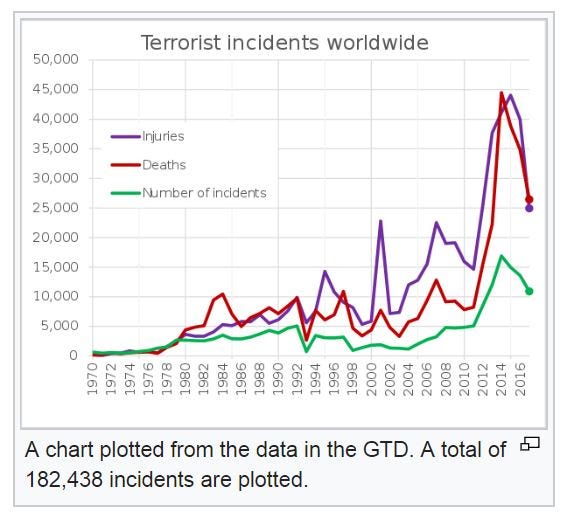

Figure 1: GTD Terrorist Incident and Death Counts since 1970

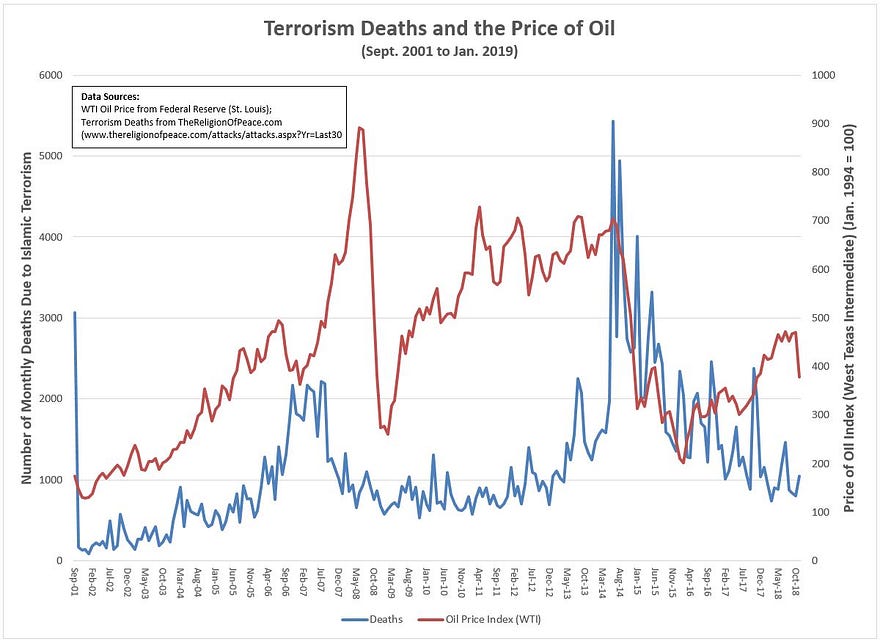

Along with the TROP database on terrorism deaths, I obtained oil price data (and other economic data) from the online data repository (FRED) maintained by the Federal Reserve (St. Louis). Figure 2 shows the terrorism death counts and oil prices (West Texas Intermediate Price Index, 1994 = 100).

Figure 2: Terrorism Deaths and the Price of Oil (2002 to 2018)

Like the GTD database, TROP shows three terrorism-related death spikes from 2001 to 2018 (blue line). The first, of course, is 9–11 (on the far left of the chart). The second is prior to and during the 2006 Iraq War surge. And the third spike occurs with the rise of ISIS in Syria starting in 2014.

The red line shows how oil prices have varied since 2002. They rose rapidly and consistently immediately after 9–11 and peaked right before the 2008 world financial crisis. Prices fell to near 2002 levels, but recovered over half of its losses from the financial crisis by the Autumn of 2014, only to decline again to near 2002 levels (in constant terms) by early 2016. Oil prices had been recovering since then, but have fallen precipitously since October 2018.

WTI is selling for $51.45-a-barrel as of 2:00pm (January 11, 2019). WTI crude was just over $100-a-barrel in 2014.

Testing the Hypothesis

Sometimes the eyeball test is all you need. And, in this case, it helps but isn’t quite enough. What jumps out to me are three distinct periods where terrorism deaths and oil prices appear tightly (and positively) linked.

The first is from early 2002 to July 2007. After that, the two series move in opposite directions from late 2007 until late 2010, when they start moving in the same direction again. As ISIS became a significant factor in Syria in mid-2014, an extreme spike in terrorism deaths occurs and is not reflected in oil prices. However, after the initial noise generated by ISIS, around late 2014 the two series move in a strong lock-step fashion until late 2015.

To more formally test the relationship between terrorism deaths and oil prices, I estimated a simple linear regression model (I also tested a Poisson regression model — which is more appropriate for count data — and found similar results to the linear model. For simplicity of interpretation, I am reporting the linear model here).

Along with oil prices, I included statistical controls for serial autocorrelation (terrorism deaths lagged by one time period) and the expected impact a strong world economy might also have on the cash reserves of oil-producing Gulf states. Though originally collected at the monthly level, the data in the following model are at the quarterly level.

Other variables tested but found to be insignificant predictors of worldwide terrorism deaths were: Number of U.S. Troops Deployed to Iraq/Afghanistan/Syria, OPEC Oil Production, OPEC Oil Supply, U.S. Dollar Value Index and U.S. DoD Terrorism/War-related Budget.

Methodological Note: Including a lagged dependent variable, as I did, can sometimes soak up significant explanatory variance causing other independent variables, that may be still be significant predictors of terrorism deaths, appear insignificant. For the exercise here, however, I was comfortable with that risk given that oil prices remained statistically significant across the various tested models despite the presence of the lagged dependent variable. I am therefore confident in saying: “Oil prices and terrorism deaths are significantly and positively related (in this time period).”

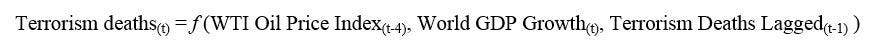

The linear model tested was a follows:

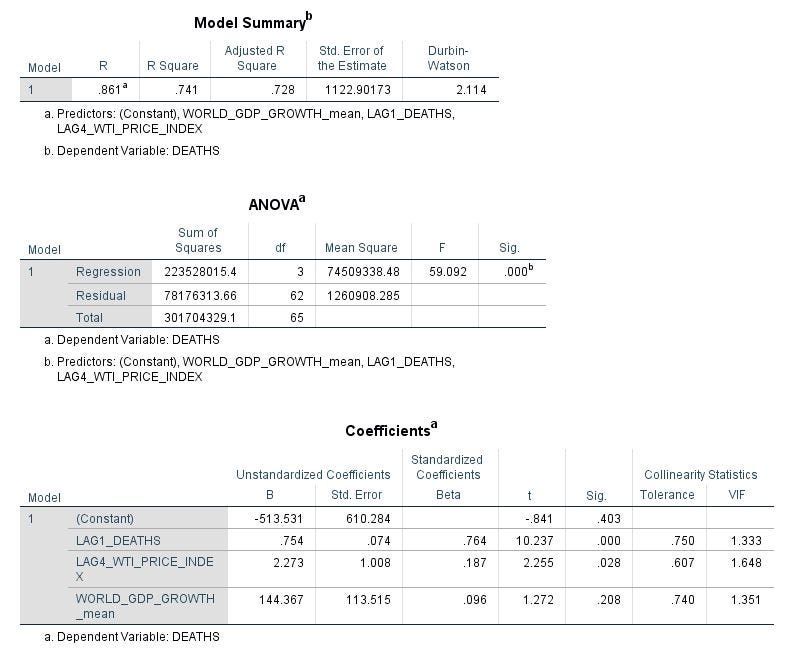

The parameter estimates and statistical tests shown in Figure 3 were generated in the SPSS software package. The ‘Model Summary’ table indicates 74 percent of the variance in terrorism deaths can be accounted through our simple three-variable model. Not bad.

The third tables shows the parameter estimates and indicates that the oil price variable (WTI PRICE INDEX lagged 4 quarters) is significantly and positively related to terrorism deaths (b = 2.27, p = 0.028). In other words, for every 1-point increase in the WTI crude oil price index, there are 2.27 additional terrorism deaths per quarter. Keep in mind that the WTI Oil Price Index ranged between roughly 100 and 1000 points during this period with a standard deviation of 172. A one-standard-deviation increase in oil prices therefore could result in 390 additional terrorism deaths.

Also note that lag structure for oil prices. Apparently, it takes four quarters (one year) for an oil price level to impact terrorism deaths, suggesting this is the length of time between a decision to sell oil assets, distribute funds to militant groups, and operational activities by the militant groups.

Figure 3: SPSS-generated linear model estimates

Do we really believe oil prices are closely linked to terrorism levels?

Honestly, I was very skeptical going into this statistical exercise, despite the strong anecdotal evidence (such as the 2009 U.S. State Department Report) and the visual evidence from the time-series charts.

I still believe the relationship is more complicated than oil price and the amount of discretionary money in Saudi pockets. For one, while the Saudis are still almost entirely dependent on the sale of oil for their cash reserves, there are other investments in their portfolio (which is why I included worldwide GDP growth in the model).

Geopolitical strategic interests, independent of oil prices, also drive Saudi money (and the money of other oil-producing Gulf states) into the bank accounts of Islamic militants.

The Saudi’s still perceive Iran to be its biggest strategic threat and, for that reason, a better specified model explaining terrorism deaths should include year-to-year measures of the intensity of the Saudi-Iranian conflict. I this exercise I have not accounted for that major factor.

There is also a religious/ideological component to terrorism that is not considered here. As long as seemingly permanent U.S. military bases are sprinkled all over the Arabian peninsula, including the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the region will be an incubator of anti-West militancy.

Still, there is no doubt in my mind that stagnant and falling oil prices are hurting Islamic militant organizations and I believe there is sufficient evidence, quantitative and qualitative, to support that conclusion.

If oil prices should rise again (and they will, at least until we stop using so much cheap Middle East oil), will terrorism rebound?

If Morris is correct, the U.S. military and security establishment is skeptical of terrorism’s resurgence moving forward:

“Almost two decades the Department of Defense and its enablers have been focused on Islamic terrorism. For years the metastasized military-industrial complex sent tons of money and personnel sloshing towards anti-Islamic organizations like the Gatestone Institute and Jihad Watch. Some of that still definitely goes on, but it came to a sort of symbolic end in January of 2018. That month saw the release of the new national defense strategy. To quote directly, ‘Interstate strategic competition, not terrorism, is now the primary concern in U.S. national security.’”

Interstate strategic competition?

I wonder if that will cost as much to fight as it did to fight terrorists over the past 17 years?

Why do I even have to ask?

- K.R.K.