By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; February 12, 2019)

Political scientists have long accepted that the formation of a viable third party in the U.S. is inhibited by its winner-take-all (simple-majority, single ballot) electoral system.

At the presidential-level, the electoral college doesn’t help either.

Yet, most voters, at some point disenchanted with the nominees of the two major parties, have probably dabbled with the thought of voting for a third-party candidate.

Actually voting for a third-party candidate rarely ever happens.

In his 1963 cross-national study of electoral systems, Political Parties, French sociologist Maurice Duverger concluded:

The simple-majority single-ballot system favours the two-party system…this approaches the most nearly perhaps to a true sociological law.

Until recently, Durverger’s Law had been one of political science’s few durable laws. In recent years, however, research by Patrick Dunleavy and Rekha Diwakar argues that the dominance of the two-party system in the U.S. cannot be explained by Durverger’s Law or its later derivatives. The U.S. two-party system is unique from a cross-national perspective.

Regardless of how we explain the entrenchment of the U.S. two-party system, the electoral evidence says third parties do not perform well in the U.S., particularly at the presidential level where local- and state-level party organizations are critical to a party’s national success.

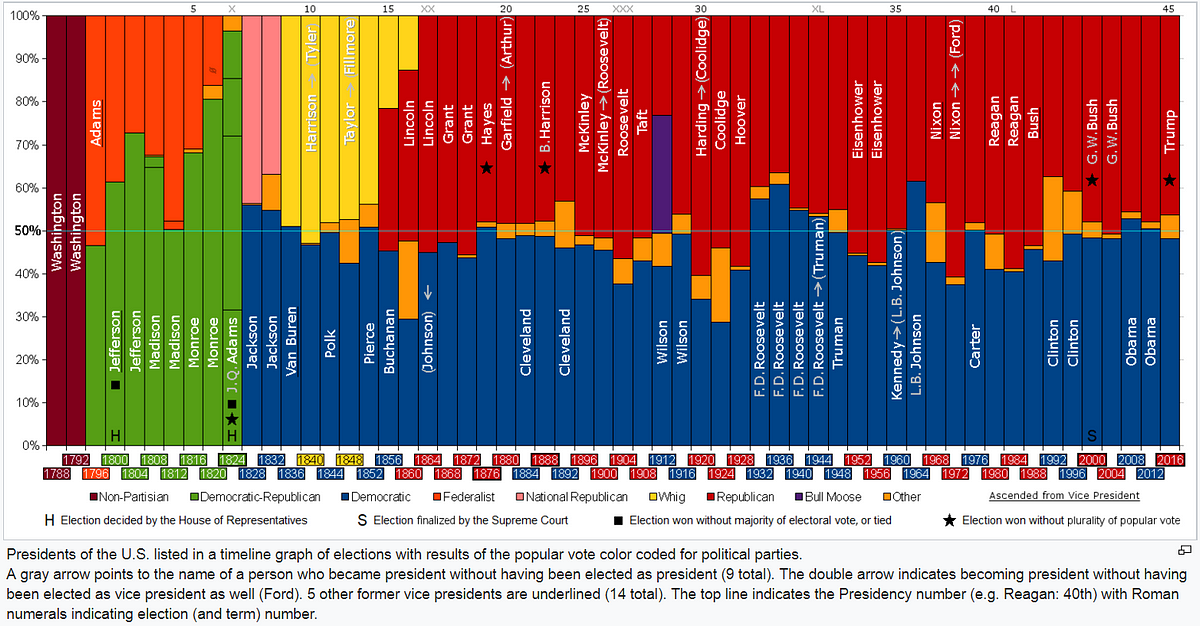

Across all U.S. presidential elections, Figure 1 illustrates the general failure of third party candidates (the orange bars and one purple bar) to even come close to winning a majority of the popular vote.

Figure 1: Presidential votes by party

Instead, where third party candidates such as Teddy Roosevelt (Bull Moose Party, 1912) and Ross Perot (1992) arguably have been successful, is in splintering a majority party enough to allow a minority party candidate to win. Roosevelt pulled in 25 percent of the popular vote in 1912, effectively preventing President William Howard Taft, the Republican incumbent, from winning re-election. Likewise, Ross Perot’s maverick candidacy in 1992 garnered 19 percent of the popular vote and may have done the same to President George H. W. Bush’s re-election chances.

Voter disenchantment with an incumbent administration and an unacceptable alternative from the other major party seems to drive the emergence of meaningful third-party challenges.

Will we see a significant third-party challenger in the 2020 presidential election?

The current presidential election season is already inspiring predictable calls for a new third-party alternative to challenge Donald Trump and whomever the Democrats nominate. So far, the two most common scenarios are:

(1) Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz (or, perhaps, former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg) running as an independent candidate in contradistinction to a Democratic Party he views as becoming too leftist.

(2) Should their preferred candidate not win the Democratic Party nomination, progressive Democrats could leverage Sanders’ expansive national infrastructure to run a third party candidate, not only for the presidency, but for congressional, state, and local elections as well.

The latter would be far more disruptive to the two-party system as a Schultz candidacy would inevitably fail and leave no residual organizational structure to build a viable third party for the future.

Sanders, on the other hand, has a national organizational structure independent of the Democratic Party and could be a credible electoral force at all governing levels.

But even a Sanders third-party run might face considerable resistance from some of his own supporters and end up, in the end, getting Donald Trump re-elected. Not a result most Sanders supporters or establishment Democrats want to see.

FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver recently detailed the limitations of a Sanders candidacy in building a majority coalition for the Democratic nomination.

In Silver’s model, there are five constituencies within the Democratic Party (Loyalists, the Left, Millennials, Blacks, and Hispanic/Asian) and a candidate must win three of the five to win the nomination. According to Silver, Sanders’ appeal is strictly limited the ‘the Left’ and ‘Millennials,’ whereas, California Senator Kamala Harris and Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke have strong appeal within at least three of the five groups. [I can’t resist pointing out that Sanders has for the last three years consistently out-polled Donald Trump in a hypothetical head-to-head contest.]

Given the current political culture, a third party would most likely form around an identity characteristic such as race or ethnicity

The previously mentioned third-party scenarios are predicated on a partisan-ideological split between the third-party candidate and the Democratic Party. In the case of Schultz, his candidacy would aim to capture the ‘silent’ majority in the ideological center of American politics; while, in Sanders’ case, his candidacy would be the jettisoning of the Democratic Party’s centrist, corporate elements.

But both of these scenarios assume most American voters are ideologically driven when they walk into the voting booth.

They are not. They are partisan. They are tribal. Their are full of social group antagonisms. But they are not ideological.

In their 2017 book of American public opinion, Neither Liberal nor Conservative, political scientists Donald Kinder and Nathan Kalmoe conclude that “the ideological battles between American political elites show up as scattered skirmishes in the general public, if they show up at all.”

According to Kinder and Kalmoe, partisan preferences and attitudes arise “less from ideological differences than from the attachments and antagonisms of group life.” And this summary of ideology in America has been consistent since political scientist Philip Converse’s study of American public opinion in the 1950s.

When Brigham Young political scientists Michael Barber and Jeremy Pope looked at Trump voters they found that the claim of party loyalists as being conservative was suspect and that “group loyalty is the stronger motivator of opinion than are any ideological principles.”

The findings of Kinder, Kalmoe, Barber and Pope reinforce the work of Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels who detailed in their 2016 book, Democracy for Realists, that most voters make decisions on the basis of their social identity and partisan loyalties rather than any coherent ideology. When a favored party changes course, like driftwood, American voters do as well. The opinions of an ideologue, in contrast, is not supposed to be so pliable.

Instead, Americans are more partisan than ever as they continue to sort themselves out between Republicans and Democrats. And while more Americans than ever are calling themselves “independents” according to the Gallup Poll, it turns out these non-aligned partisans are often as partisan, if not more so, than committed partisans.

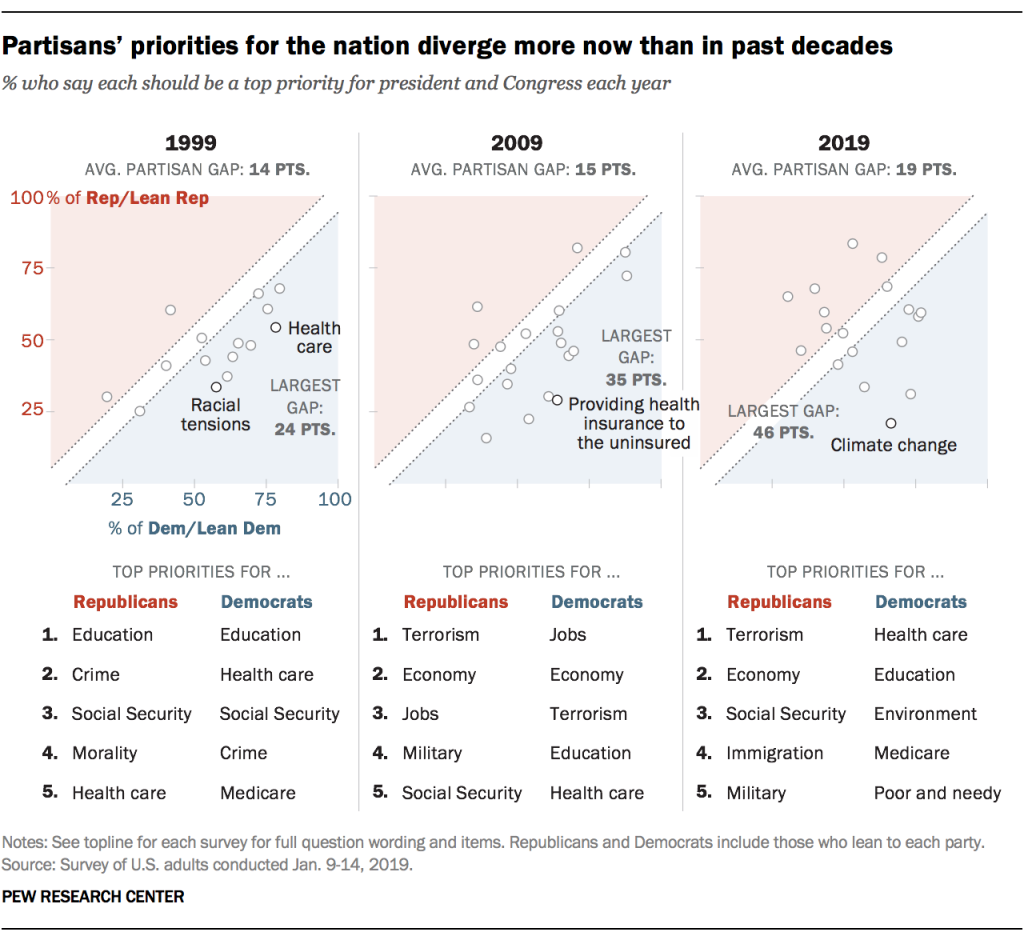

This growing partisanship is particularly evident in Americans’ issue priorities.

“Republicans and Democrats have long held differing views about policy solutions, but throughout most of the recent past there was rough partisan agreement about the set of issues that were the top priorities for the nation,” according to Pew Research’s Bradley Jones. “However, that is less and less the case. Republicans and Democrats have been moving further apart not just in their political values and approaches to addressing the issues facing the country, but also on the issues they identify as top priorities for the president and Congress to address.”

As recently as 2014, Democrats and Republicans generally put the same issues on the top of their agendas (i.e., the economy, health care, and national security). Today, not so much.

A viable third party will need to built on something other than ideology — most likely, race and ethnicity

Party ideologies can change from election to another. Remember when Republicans were the free trade party?

What doesn’t change is racial and ethnic identity.

If a sustainable third party is ever to form in the U.S., it will most likely be built upon a construct like race and ethnicity that doesn’t change so easily.

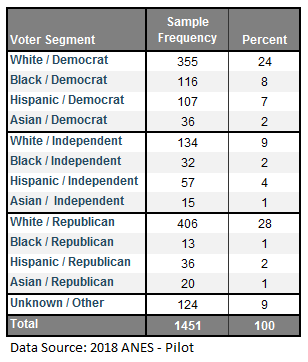

The 2018 American National Election Study (ANES), a December 2018 online survey of 2,500 eligible voters in the U.S., offers evidence that Hispanic Americans do not map onto the current two-party system as well as other Americans and could potentially support a durable third party in the near future.

Figure 2 indicates that Hispanics predominately identify as a Democrat (54%) or as an independent (31%).

Perhaps working against the idea of an Hispanic-based party is that Hispanics only account for about 13 percent of eligible voters (see Figure 2) and are the majority in only 30 U.S. congressional districts (of which 23 are represented by a Democrat).

Figure 2: Eligible Voter Segments in December 2018

Favoring the idea of an Hispanic-based party is the population growth trend which, according to the U.S. Census, will find Hispanics accounting for close to 30 percent of the total U.S. population by 2060.

But for a such a party to form, it must fulfill an unmet need. After all, if the Democratic Party substantively serves the interests of Hispanic Americans, what would be the point in carving out a new party?

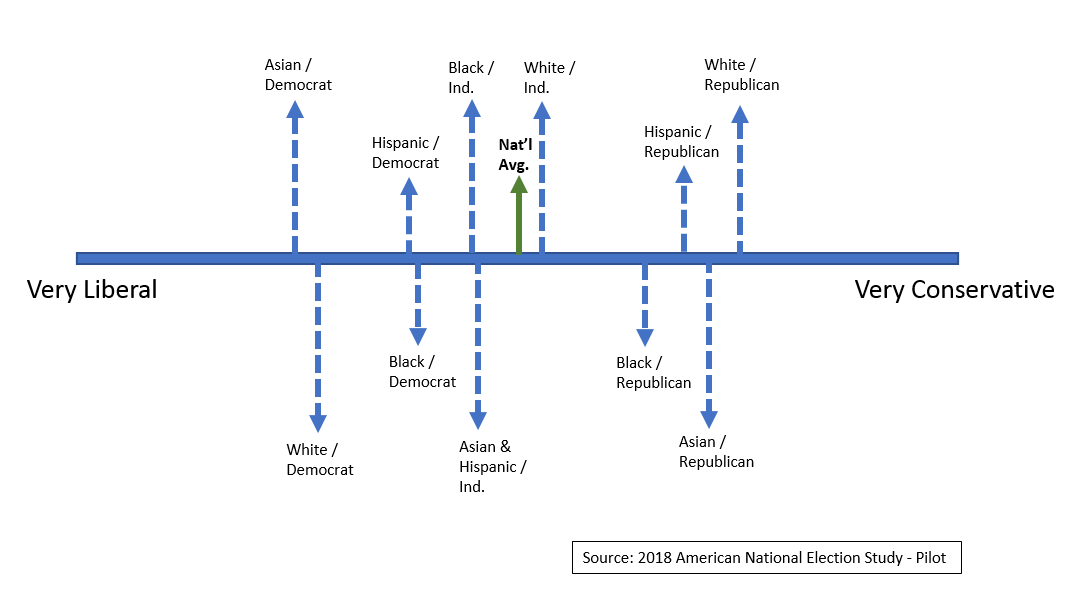

Figure 3 gives some indication that Hispanic Americans do not self-identify the same way as white Americans do along the ideological spectrum. Hispanic Democrats see themselves as less liberal than white Democrats and Hispanic Republicans see themselves as less conservative than white Republicans.

This is more true for Black Americans, but as writer and scholar Theodore Johnson aptly notes from his own quantitative research, “The social conservatism of blacks does not affect voting behavior in presidential elections, even though religiosity is strongly correlated with partisanship.”

Figure 3: Average Ideological Position of Eligible Voter Segments (Dec. 2018)

In a previous essay on NuQum.com, using 2016 ANES data, I detailed how Hispanic Americans are more centrist in their attitudes than liberals on issues ranging from transgender bathroom laws, marriage equality, and abortion rights.

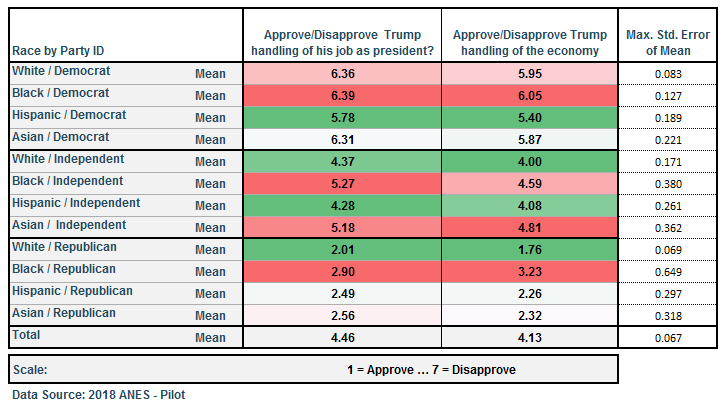

This pattern is also revealed in the 2018 ANES data (see Figure 4). Hispanic Democrats are more likely than Black or white Democrats to approve of Trump’s handling of his job and the economy

Figure 4: Presidential Approval by Eligible Voter Segments (Dec. 2018)

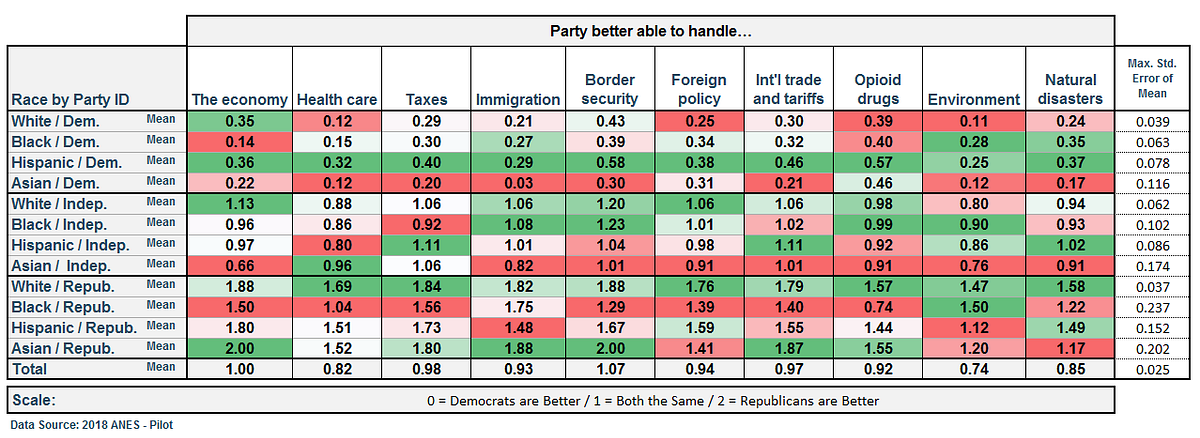

When comparing the ability of Democrats versus Republicans to handle a broad range of issues from the economy to natural disasters, Hispanic Democrats uniformly are less inclined than white, Black or Asian Democrats to think the Democrats are better (see Figure 5, where higher values indicate a stronger belief Republicans are better at handling a specific issue). An analogous pattern does not exist between Hispanic Republicans and other Republicans.

Figure 5: How the Eligible Voter Segments Rate the Two Parties by Issue (Dec. 2018)

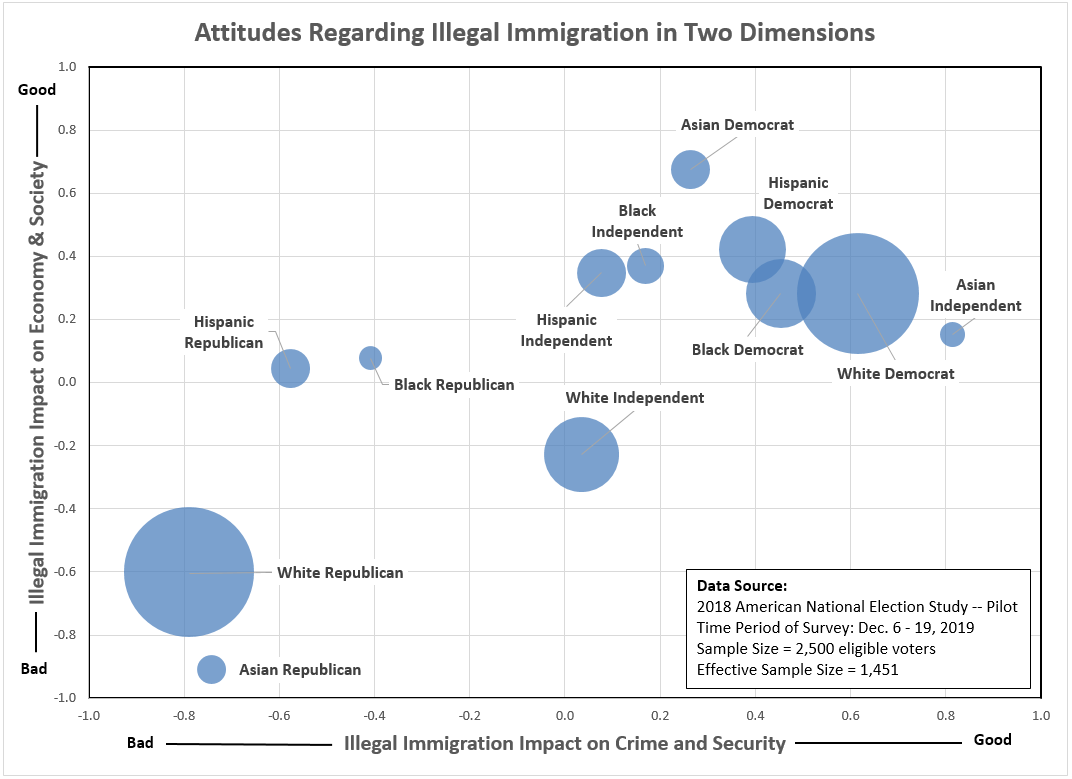

Our final graph (Figure 6) plots the attitudes of 2018 ANES respondents on a series of questions related to illegal immigration. The list of questions can be found here. To simplify the analysis, I employed a principal components analysis to identify the two most significant factors in describing attitudes on illegal immigration. The two factors were: (1) illegal immigration’s impact on the economy and society, and (2) its impact on crime and security. The two factors account for almost 70 percent of all variance in attitudes related to illegal immigration.

Hispanic Republicans are plainly unique in their attitudes regarding illegal immigration. While they are similar in attitudes with their Republican brethren on the negative impact of illegal immigration on crime and security, Hispanic Republicans differ substantially on attitudes related to the economic and social impact of illegal immigration.

Figure 6: Immigration Attitudes and Opinions across Eligible Voter Segments (Dec. 2018)

I suspect one reason the Trump administration is emphasizing the ‘crime’ aspect of illegal immigration (i.e., drugs and gangs) over the economic impact is based on the relationships observed in the 2018 ANES. For Hispanic Republicans, illegal immigration is about crime, not the economy.

As for Hispanic Democrats, they differ slightly from white Democrats on the impact of illegal immigration on crime, while both groups see illegal immigration as a more positive factor on the economy and society.

Are these attitudinal differences enough to inspire an Hispanic third party?

Hispanic Democrats are more socially conservative and family-oriented than the average Democrat. Hispanic Republicans differ significantly from other Republicans on illegal immigration’s impact on its economic and social benefits.

Are these differences enough to inspire Hispanic Americans to jettison the current two-party system and build a third party that better represents their attitudes and opinions?

The safe and unimaginative answer is NO.

From data’s dispassionate perspective, however, it is hard to see how Hispanics believe their interests are sufficiently served under the current two-party system.

According to the opinion data, Hispanics are more socially-conservative and family-oriented than Democrats and more accepting of illegal immigration for economic and social reasons than the Republicans.

A third party dedicated to the interests of social conservatism and a more rational immigration policy might very well attract a large enough fraction of American voters to be the deciding factor in future presidential elections and a meaningful number of congressional and state-level races.

We can at least conjecture.

- K.R.K.

Comments and critiques can be sent to: kroeger98@yahoo.com