By Kent R. Kroeger (NuQum.com, August 8, 2019)

Medicare-4-All was the discriminating issue in the last two Democratic debates with Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren the most vocal proponents and the remaining candidates (less Hawaii Representative Tulsi Gabbard and New York Mayor Bill de Blasio) taking up the opposition.

To likely Democratic primary voters watching the two debates, Elizabeth Warren’s performance was particularly strong — though Tulsi Gabbard’s Cool Hand Luke impersonation offered us the best moment from either debate when she calmly exposed Senator Kamala Harris’ record as California Attorney General as incompatible with her presidential stump speech rhetoric. How could Kamala have been so unprepared to defend her own record?

However, most striking about the debate were the candidates relying on historically conservative talking points to dismiss not just Medicare-4-All, but the Green New Deal and college debt forgiveness, among other progressive policy priorities. At one point during the debate, my wife asked if Republicans were also being included in the debate. “No, honey. John Delaney is a Democrat.”

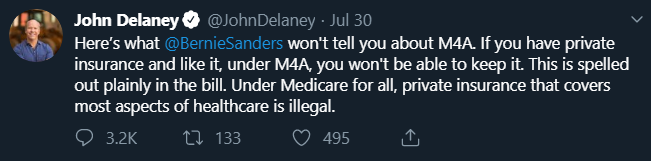

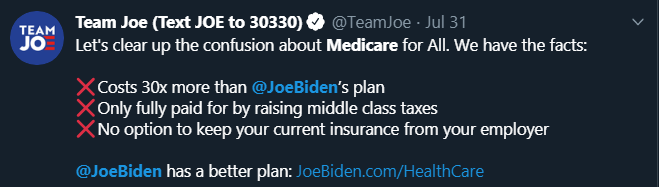

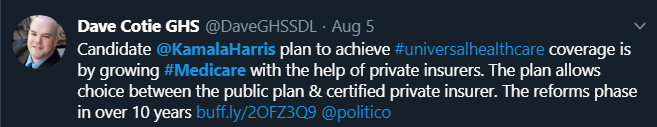

The Twitter accounts of these “Democrats” croon love poems to private insurance companies, market capitalism and ‘choice,’ while mixing in enough disinformation about progressive ideas to truly confound anyone trying to understand the disputed issues.

This is how they talk about Medicare-4-All:

The Republican National Committee couldn’t have written Tweets as dishonest as those about Sanders’ Medicare-4-All plan — a plan a Koch Brother-funded think tank concluded would reduce total U.S. health care spending by about $2 trillion over 10 years, relative to the current healthcare system. That is likely an under-estimate of the savings from Medicare-4-All.

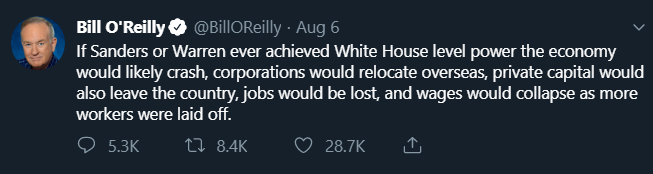

A note to Joe Biden, Kamala Harris, Tom Perez and the Democratic National Committee: You know your party is out of energy and ideas when the talking points for some of your leading presidential candidate could pass for something Bill O’Reilly might write:

If you don’t believe our country can afford universal healthcare for all or that we can get off fossil fuels sooner rather than later, you are not a Democrat anymore. You are a Republican. Which is fine. There is a party for that.

There is nothing wrong with Republicans running as Democrats and Democrats running as Republicans (though I cannot think of a single example in my lifetime of the latter happening…John Anderson in 1980?).

Who has the right to tell anyone what party they should belong to. This is a democracy after all? Right?

Who is driving the Democratic Party train?

Years ago, the first assignment I gave undergraduate students in my introductory political science classes was to describe, in a short paragraph, how the American democracy works.

The students’ paragraphs were earnest, typically focusing on voters and elections and describing a system where people’s policy preferences are reflected, if only loosely, in the policies passed by their elected representatives. Most of the students’ paragraphs were held aloft with Jeffersonian/Madisonian language (‘all people created equal,’ ‘liberty,’ ‘consent of the governed,’ ‘freedom’) and mixed with a healthy dose of American exceptionalism (‘the freest country in the world’).

But there would always be at least one student that would write something along these lines:

We don’t live in a democracy. The corporations pick the candidates and the government reflects corporate interests.

No, Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez was never in one of my classes — She was a toddler when I taught at the university-level.

As a young instructor, I felt a duty to guide students away from cynical views on our democracy and towards something realistic, but also optimistic. In one the class slides I provided a definition of democracy by which to judge the American version:

A government, existing at the consent of the people, who, through elected representatives, satisfy these conditions: (1) Full participation — all citizens are included in the political system and have the capacity to participate, (2) Voting equality — each citizen’s vote is equal to another’s, (3) Full knowledge of choices — citizens understand all available political choices, (4) Popular agenda control — citizens control the political agenda.

The paragraph was just a reformulation of political scientist Robert Dahl’s definition of an ‘ideal’ democracy from his 1989 book, Democracy and Its Critics. As an exemplar, no democracy could meet Dahl’s idealized version, and that was his point. All democracies are imperfect, some more so than others.

My conclusion at the time was the American democracy, while flawed, fulfilled all four of those observable conditions.

Over the years, however, my views have crept closer to the cynical view, perhaps to an even darker place. And nowhere has my own cynicism grown darker than when observing the corporate news media’s current role in the democratic process.

The recent Democratic debates are illustrative. In the July 31st debate sponsored by CNN, former Vice President Joe Biden spoke for 22.5 minutes, Senator Kamala Harris for 17 minutes, and Senator Cory Booker for 13 minutes. The other seven candidates each spoke between 9 and 11 minutes. These differences are not products of chance. The debate was designed by CNN to give the top 2 or 3 candidates — in terms of polling numbers — the most face time with the 11.3 million Americans viewing the debate. Campaigns will pay around $200,000 for only 30 seconds on a national cable TV network. In essence, CNN gifted Joe Biden about $4.5 million in advertising and to Harris about $2.5 million.

Lesser known presidential candidates already struggle to gain traction with voters and donors. By tilting the process towards the “popular” candidates, CNN is effectively enforcing an Overton window among political candidates.

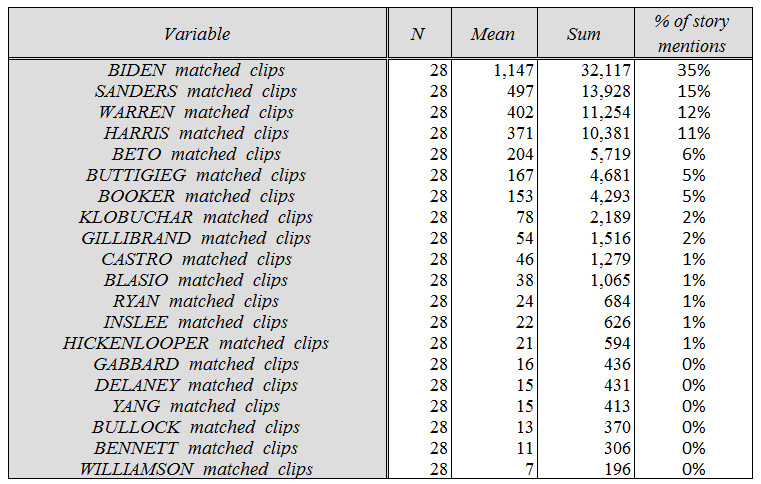

The cable news media’s sentinel role is apparent when looking at its coverage of the 2020 Democratic nomination candidates over the first seven months of the race (see Figure 1). Over that period, Biden has received 35 percent of all candidate mentions, followed by Sanders (15%), Warren (12%), and Harris (11%). A significant drop-off occurs after that, as almost three-quarters of mentions go to the top four candidates. That may be the maximum number candidates a news network can handle at one time.

Figure 1: Weekly cable news clips from Dec. 30, 2018 to July 21, 2019 (28 weeks).

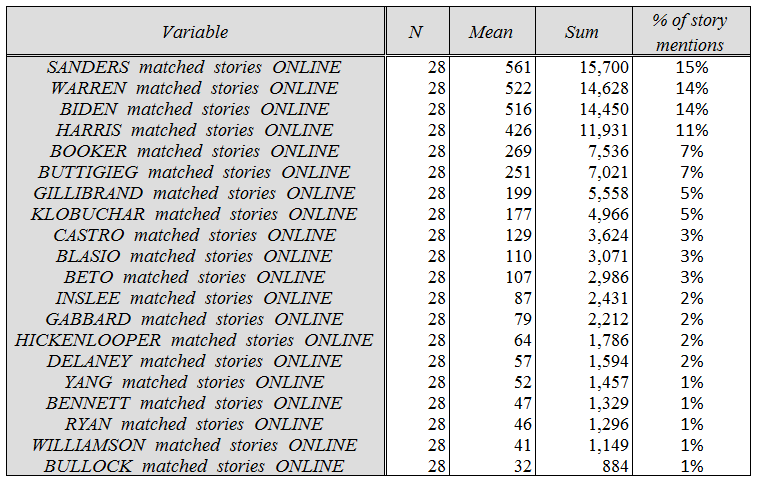

A different relationship exists for online news candidate mentions (see Appendix Figure A.1), as there is no clear leader and the top four candidates are more bunched together. Over the same seven-month period, Sanders received 15 percent of all candidate mentions, followed by Warren (14%), Biden (14%), and Harris (11%).

Is it wrong for cable news networks to be political gatekeepers? Isn’t that one of the core functions of the press? Who wants to learn about John Delaney or John Hickenlooper or Michael Bennet if they don’t need to?

There is a strong argument rooted in microeconomic and decision theory literature that journalists should be filtering out minor candidates and focus their reporting on more viable ones. There are over 20 Democratic candidates, after all. We can’t possibly get to know every one of them with any meaningful depth. The cable networks are providing a genuine service when they ignore some candidates and direct their attention towards others.

“Somewhere, somehow, professional journalists have to decide who gets covered — and any formula they could choose is going to appear biased to someone,” concludes journalist Jonathan Stray. “In the end, the candidates who attack the media are right about one thing: The press is a political player in its own right. There’s just no way to avoid that when attention is valuable.

Yet, why don’t I trust the cable networks and now the high tech and social media companies to make these decisions?

I think back to my most cynical students. How can we defend a democratic system that systematically marginalizes voices outside the mainstream? Perhaps we don’t live in a democracy. Perhaps the corporate news organizations really are the ones picking our presidential candidates and Election Day is simply a tool to legitimize the their choices.

An over-simplification? Obviously. Wholly inaccurate? I think not. And is this power restricted to the corporate news media? Absolutely not, as the high tech and social media giants also have become active participants in the American electoral system and evidence of their power is rapidly being documented by researchers.

Is Google already too powerful?

Speaking at New York City research summit in January 2013 organized by Google, Robert Epstein, a Harvard Ph.D. in psychology and behavioral sciences, said, “Google has likely been determining the outcomes of upwards of 25 percent of the national elections worldwide since at least 2015.”

The same academic, testifying in mid-July before the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution, said that Google’s search algorithm produces a Search Engine Manipulation Effect (SEME) which likely changed vote decisions among undecided voters in 2016 to the net benefit of 2.6 million votes for Hillary Clinton. Looking towards the 2020 election, Epstein testified:

“SEME…leaves people thinking they have made up their own minds, which is very much an illusion. It also leaves no paper trail for authorities to trace. Worse still, the very few people who can detect bias in search results shift even farther in the direction of the bias, so merely being able to see the bias doesn’t protect you from it. Bottom line: biased search results can easily produce shifts in the opinions and voting preference of undecided voters by 20 percent or more — up to 80 percent in some demographic groups.”

Skepticism is always advisable before accepting social science findings, but shouldn’t the burden of proof be on Google, rather than social scientists, to show that the SEME does not systematically alter election outcomes? Can you imagine if pharmaceutical companies were allowed to market drugs to the public before doing research on their safety? No, of course not. So, why should the standard be different for Google or the giant social media companies?

But before we go to Mountain View, California, breaking down the doors at Google headquarters to seize their search algorithms — which we should do at some point — let us not forget the older and probably bigger dog in this fight…television news, particularly the cable networks (CNN, MSNBC and Fox News).

Political science research has generally found that national news outlets are powerful actors in shaping our political environment (Summaries of this research can be found here, here, here and here). Not only do the media expose us to events and people we would not otherwise experience directly, they frame and interpret the political world for us as well — and that may be their greatest influence on our political system: Frame the policy agenda and change the electoral outcome.

But don’t take academia’s word for the importance of the news media on politics — just ask Jeff Zucker, president of CNN, about his news network’s role in the election of Donald Trump in 2016.

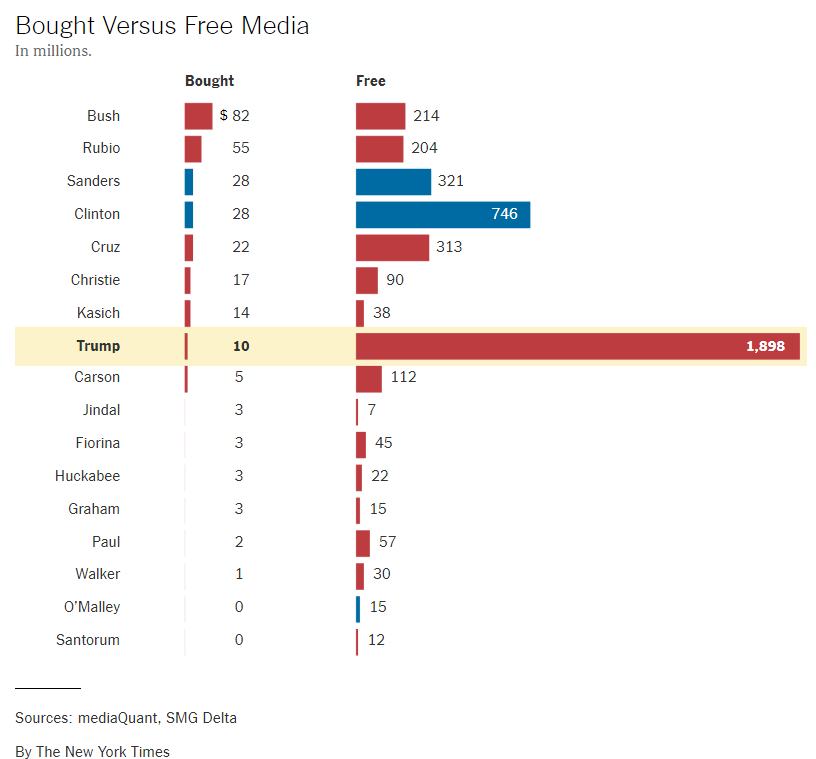

While stopping short of saying CNN unduly influenced the 2016 election outcome, in a 2018 CNN interview with former Barack Obama adviser David Axelrod, Zucker admitted his network televised too many Trump election rallies unfiltered and in their entirety. No other 2016 candidate was gifted so much free publicity — some estimates indicate Trump received a $1 billion advantage over Hillary Clinton in free media coverage. More certainly, Trump’s challengers for the 2016 Republican nomination never had a chance to gain traction with voters as long as CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News kept broadcasting Trump rallies live (see Figure 2). In another study, researchers found that CNN, specifically, provided Trump with eight times as much coverage as the number two candidate in the 2016 Republican nomination race, Ted Cruz.

Figure 2: Bought versus Free Media in the 2016 Presidential Election

“I do not believe that’s why he’s president of the United States,” Zucker told Axelrod. “A lot of people want to assign that blame to us and to me. If only we had that much power, especially on the Republican side. I do not believe that’s why he’s president of the United States. But I do think we made a mistake.”

Zucker is being too modest. Along with MSNBC, headed by Zucker’s former understudy, Phil Griffin, CNN showered Trump with attention from the moment Trump came down the escalator at Trump Tower to announce his candidacy. They may not have realized what they were doing — in part, because many at the news networks believed Trump was more of a sideshow than a serious presidential candidate — but by the time it became apparent Trump had a punchers chance of winning the presidency over Clinton, the damage had been done.

In an interview with TheWrap.com last year, media critic Stephen Miller said, “There is no figure in media more responsible for Donald Trump’s legitimacy in media, which led to his rise in politics and to the presidency, than Jeff Zucker.”

And you thought the Russians and their $100,000 Facebook advertising buy elected Trump.

Candidate popularity and cable news coverage move in lock-step

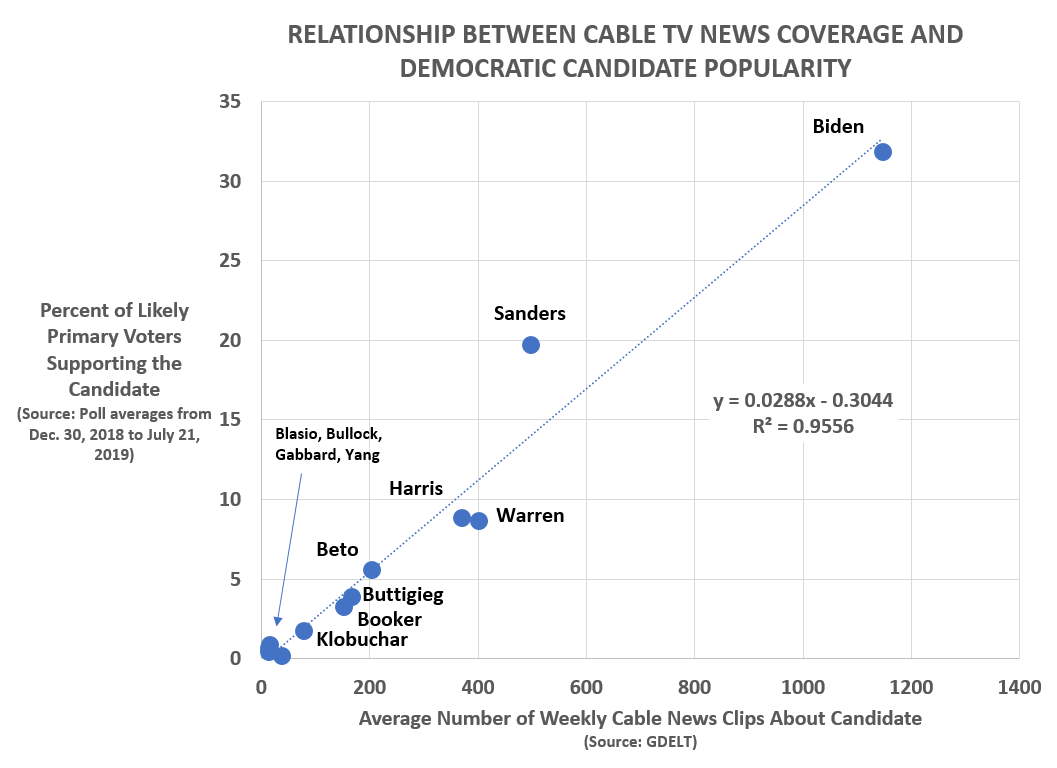

A cross-sectional analysis of recent data from RealClearPolitics’ presidential poll databases, cable news content (i.e., candidate mentions) from the GDELT project, and Google search trends data reveals the strong relationship between the cable news media and candidate popularity. And we also see evidence of a relationship between candidate popularity and Google search trends. This first relationship is not news. Data journalist pioneer Nate Silver and other researchers have measured the strong relationship between cable news and candidate popularity.

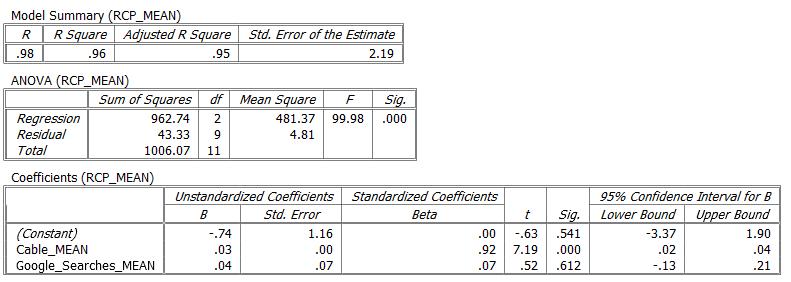

In my 2020 Democratic nomination data, cable news coverage of candidates explains 95 percent of the variance in average levels of support between Dec. 30, 2018 and July 21, 2019 for the 12 candidates in my dataset (see Figure 3). All candidates are near the regression line — the only exception being Sanders who over performs in popularity given his level of cable news coverage. One explanation for that could be that Sanders is a known quantity given his 2016 presidential run and the news media doesn’t find him as ‘newsworthy.’ However, Biden is perhaps even better known than Sanders, yet his news mentions and public support level are well explained by the regression model. Sanders is most likely different for reasons other than just name recognition.

Figure 3: Cable TV news coverage and Democratic candidate popularity

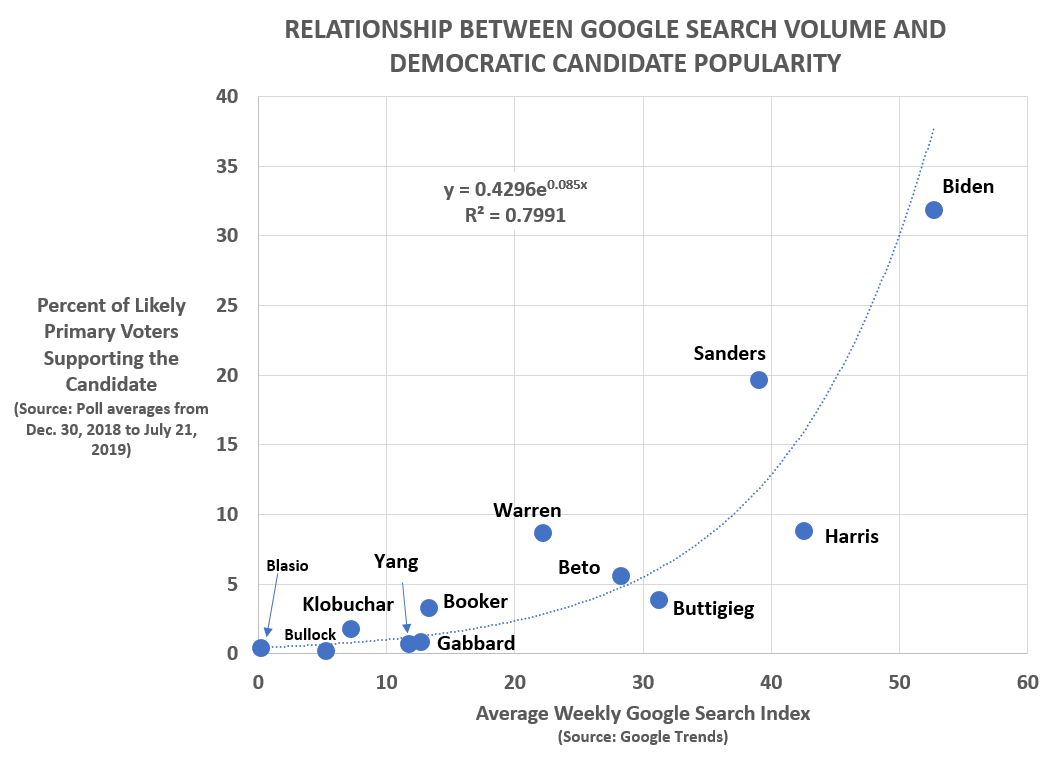

In contrast, Google search volume, while highly correlated with candidate popularity (see Figure 4), does not offer any new information regarding candidate support. When both cable news mentions and Google searches are included in the same regression model as explanatory variables, only cable news mentions maintains statistical significance (see Figure A.3 in the Appendix below). Google search volume also appears to have a diminishing return on candidate popularity as a search volume’s relative index approaches 100 (its maximum possible value for any single candidate).

Figure 4: Google search volume index and Democratic candidate popularity

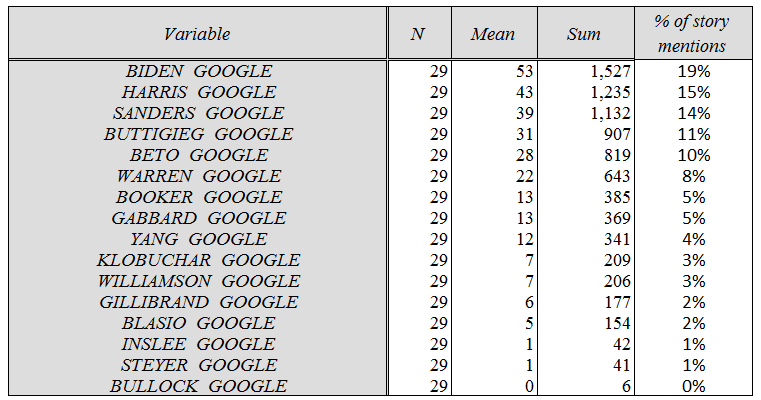

Interestingly, Google search volume on candidate names generates a divergent candidate ordering from the amount of cable/online news coverage a candidate receives (see Appendix Figure A.2). Since late-December 2018, Biden has received 19 percent of all candidate name searches on Google, followed by Harris (15%), Sanders (14%), South Bend, Indiana Mayor Pete Buttigieg (11%) and Senator Beto O’Rourke (10%). New candidates receive relatively more attention on Google than they do within the news media.

It is important to note that my data cannot tell us much about the direction of causation. Is media coverage causing candidate popularity? Or is candidate popularity driving media coverage? The answer is likely that both statements are true, which could explain why the correlation between the cable news coverage and popularity is is so strong. As a candidate becomes more popular, the cable news media adjusts their own coverage to meet the apparent public demand. Similarly, a candidate’s popularity can rise dramatically when cable news dedicates its coverage to a relatively unknown candidate —Mayor Buttigieg is a good example.

We haven’t even mentioned the role of big donors within the Democratic Party. Harris famously courted Hillary Clinton’s mega-donors in the Hamptons in Summer 2017, a time when she was relatively unknown nationwide. Any understanding of the nomination process cannot ignore where the money comes from and the expectations that follow.

“Maybe Harris has what it takes and will surge ahead of the pack in a few years to win the right to dethrone Donald Trump,” The Guardian’s Ross Barkan wrote two years ago. “It’s too early to tell. But her Hamptons gallivant with Clinton plutocrats is a dispiriting reminder that the Democratic party thinks all can be as it once was, and the status quo isn’t worth being ruffled. Donors can still vet candidates and propel them forward in the press. Anyone beyond the upper crust isn’t a serious agenda setter.”

It is no longer too early to tell. Yes, mega-donors can create viable presidential candidates at a brie and Chablis-filled party nestled in one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in America. Would we be talking about Harris now if the Democratic Party’s donor class hadn’t sanctioned her run? Of course not.

Should we be worried?

I refuse to contribute to the angst industry, so forgive me if I am not worried about Google now, or in the future, controlling our political system. Google picking our president is no more or less loathsome to me than CNN doing it. Cloistered elites have been picking U.S. presidential candidates since the country’s inception — why would it change now?

Still, the possibility of Silicon Valley tech czars deciding who gets access to the nuclear launch codes should not sit well with anyone. Do we resign ourselves to the notion that voters are just ancillary participants, by the Founders’ design or due to their own human limitations, in a political system where their role is more adjunctive than substantive? Are we mere driftwood being carried along in the political currents?

A 2014 study I’ve cited many times remains my bedrock evidence when arguing that the U.S. is not a democracy if the policies passed by our representatives don’t reflect our collective interests. The study by political scientists Martin Gilens of Princeton and Benjamin I. Page of Northwestern has its critics (as it should), but the daily anecdotal evidence only strengthens its core finding: “When the preferences of economic elites and the stands of organized interest groups are controlled for, the preferences of the average American appear to have only a minuscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy,” concluded Gilens and Page.

As Johns Hopkins associate professor Yascha Mounk wrote in The Atlantic, “Public policy does not reflect the preferences of the majority of Americans. If it did…Marijuana would be legal and campaign contributions more tightly regulated; paid parental leave would be the law of the land and public colleges free; the minimum wage would be higher and gun control much stricter; abortions would be more accessible in the early stages of pregnancy and illegal in the third trimester.”

At the risk of blaming the victim…

We live in a technology environment that deliberately herds news consumers to a relatively small set of news sites, despite consumers having — theoretically — hundreds of news websites from which to choose. In the process, voters have grown more partisan and less tolerant of alternative points of view.

Regina Lawrence, executive director of the University of Oregon’s Agora Journalism Center and George S. Turnbull Portland Center, cites citizens’ own selection bias as an important factor in the polarization trend. “Selective exposure is the tendency many of us have to seek out news sources that don’t fundamentally challenge what we believe about the world,” according to Lawrence. “We know there’s a relationship between selective exposure and the growing divide in political attitudes in this country. And that gap is clearly related to the rise of more partisan media sources.”

However, search engines like Google also contribute to this cycle by reinforcing people’s news consumption patterns through their profiling algorithms (i.e., your Google search history impacts what you see every time you use Google).

It doesn’t need to be this way and the best place to start changing that dynamic is by regularly putting ourselves in a position to hear perspectives much different from our own. Don’t use Google every time you search for news stories or information. Other search engines exist, such as DuckDuckGo.com and StartPage.com (both of whom protect your privacy by not storing your search history).

Information source diversity is our greatest defense against elite domination of our political system. The power of CNN, MSNBC, Fox News, Facebook, Twitter and Google, among others, to control our opinions would be significantly mitigated if we sought alternative news sources.

Forcing yourself to seek out new viewpoints sounds nice in theory but is difficult in practice. It rubs against our basic human nature. Even for myself, as I preach the importance of opinion diversity, my own news consumption patterns in the past three years have grown narrower (…does The Jimmy Dore Show even count as a news show? The fact that this is even a legitimate question indicates how far mainstream news has fallen.).

We need to fight our instinct to drift towards conformity and predictability. If we don’t, CNN, MSNBC, Fox News and Google will indeed pick our next president.

- K.R.K.

Comments and data requests can be sent to: kroeger98@yahoo.com

APPENDIX: Summary Data Tables

Figure A.1: Weekly online news clips from Dec. 30, 2018 to July 21, 2019 (28 weeks).

Figure A.2: Google search volume (on a relative scale with a maximum value of 100) from Dec. 30, 2018 to July 29, 2019 (29 weeks).

Figure A.3: Linear regression model for RCP poll average (Dec. 30, 2018 to July 21, 2019) with Google search relative volume and cable news coverage as explanatory variables (n=12 candidates).