By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; February 4, 2021)]

In April 1985, the Coca-Cola Company, the largest beverage company in the world, replaced their flagship beverage, Coca-Cola, with New Coke — a soda drink designed to match the sugary sweetness of Coca-Cola’s biggest competitor, Pepsi.

At the time, Pepsi was riding a surge in sales, fueled by two marketing campaigns: The first campaign was a clever use of blind taste tests, called the “Pepsi Challenge,” and through which Pepsi claimed most consumers preferred the taste of Pepsi over Coca-Cola. The second, called the “The Pepsi Generation” campaign, featured the most popular show business personality at the time, Michael Jackson. Pepsi’s message to consumers was clear: Pepsi is young and cool and Coca-Cola isn’t.

Hence, the launch of New Coke — which, to this day, is considered one of the great marketing and re-branding failures of all time. Within weeks of New Coke’s launch it was clear to Coca-Cola’s senior management that their loyal customer base — raised on the original Coca-Cola formula — was not going to accept the New Coke formula. Hastily, the company would re-brand their original Coca-Cola formula as Coca-Cola Classic.

Coca-Cola’s public relations managers tried to retcon the whole New Coke-Classic Coke story to make it appear the company planned to launch Coca-Cola Classic all along — but most business historians continue to describe New Coke as an epic re-branding failure. New Coke was discontinued in July 2002.

What did Coca-Cola do wrong? First, it never looks for good for a leader to appear too reactive to a rising competitor. On a practical level, for brands to lead over long periods they must adapt to changing consumer tastes — but there is a difference between ‘adapting’ and ‘panicking.’ Coca-Cola panicked.

But, in what may have been Coca-Cola’s biggest mistake, they failed to understand the emotional importance to their loyal customers of the original Coca-Cola formula.

“New Coke left a bitter taste in the mouths of the company’s loyal customers,” according to the History Channel’s Christopher Klein. “Within weeks of the announcement, the company was fielding 5,000 angry phone calls a day. By June, that number grew to 8,000 calls a day, a volume that forced the company to hire extra operators. ‘I don’t think I’d be more upset if you were to burn the flag in our front yard,’ one disgruntled drinker wrote to company headquarters.”

Prior to New Coke’s roll out, Coca-Cola did the taste-test research (which showed New Coke was favored over Pepsi), but they didn’t understand the psychology of Coca-Cola’s most loyal customers.

“The company had underestimated loyal drinkers’ emotional attachments to the brand. Never did its market research testers ask subjects how they would feel if the new formula replaced the old one,” according to Klein.

Is Hollywood Making the Same Mistake as Coca-Cola?

Another term for ‘loyal customer’ is ‘fan.’ In the entertainment industry, fans represent a franchise’s core audience. They are the first to line up at a movie premiere or stream a TV show when it becomes available. They’ll forgive an occasional plot convenience or questionable acting performance, as long as they can still recognize the characters, mood and narratives that make up the franchise they love.

Star Trek fans showed up in command and science officer-colored swarms for 1979’s Star Trek: The Motion Picture, an extremely boring, almost unwatchable film, according to many Trek fans. Yet, they still showed up for 1982’s Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan (a far better film) even when the casual Trek audience didn’t — helping make the Star Trek “trilogy” films (The Wrath of Khan, The Search for Spock, The Voyage Home) among the franchise’s most successful.

No superhero franchise has endured as many peaks and valleys in quality as Batman, a campy TV show in my youth, but a significant box office event with Tim Burton’s Batman (1989). Unfortunately, the franchise descended into numbing mediocrity after Burton, reaching a creative depth with 1997’s Batman & Robin, only to exceed the critical acclaim of the Burton-era films with Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy movies in the 2000s. Through all of this, Batman movies make money…most of the time.

This phenomenon is common to a lot of science fiction and superhero franchises: Star Wars, Superman, Spider-Man, Doctor Who, Alien, and The Terminator. among others. They are not consistently great, but they almost always bring out a faithful fan base.

That is, until they don’t.

Three major science fiction franchises have undergone significant re-branding efforts in the past five years, in the understandable hope of building a new, younger, and more diverse fan base for these long-time, successful franchises — not too dissimilar from what Coca-Cola was trying to do in the mid-1980s:

Star Wars

Now owned by Disney, Star Wars had its canon significantly altered in the three Disney trilogy movies from the original George Lucas-led Star Wars movies when the heroic stature of its two most iconic male characters — Luke Skywalker and Han Solo — was unceremoniously diminished in favor of new characters (Rey, Finn, and Poe Dameron). If Disney had a customer complaint line, it would have been overwhelmed after the first trilogy movie, The Force Awakens, and shutdown after The Last Jedi.

Result: Disney made billions in box office receipts from the trilogy movies, but it is hard to declare these movies an unqualified success. Yes, the movies made money, but Disney designs movies as devices for generating stable (and profitable) revenue streams across a variety of platforms (amusement park attendance, spin-off videos, toy sales, etc.). The Disney trilogy has generated little apparent interest in sequel films. At the Walt Disney Company’s most recent Investor Daylast December, whichfeatured announcements for future Star Wars TV and movie projects, not one of the new projects involved characters or story lines emanating from the trilogy movies. More telling, pre-pandemic attendance at the new Star Wars-themed Galaxy’s Edge parks at Disney World and Disneyland have seen smaller-than-expected crowds — and to make matters worse, Star Wars merchandise sales have been soft since the trilogy roll out. Be assured, these outcomes are not part of Disney’s Star Wars strategy.

Star Trek

The Star Trek franchise has launched two new TV shows through Paramount/CBS in the past three years: Star Trek: Discovery and Star Trek: Picard. Through three seasons of Discovery and one for Picard, the re-branded Star Trek has turned the inherent optimism of Gene Roddenberry’s original Star Trek vision into a depressing, dystopian future. Starfleet, once an intergalactic beacon for inclusiveness, integrity and justice, is now a bureaucratic leviathan filled with corruption and incompetence. To further distance the new Star Trek from the original Star Trek series (TOS), Discovery’s writers concocted an incomprehensible plot twist — the Seven Red Signals — in order to send the Discovery’s crew 900 years into the future, past the TOS and Star Trek: The Next Generation timelines, thereby freeing the new series from the shackles of previous Star Trek canon.

Result: As Picard has had only one season, I will focus on Discovery, which has hadthree seasons on CBS’s All Access streaming platform (though only one on the broadcast network). In its 2017 series premiere, Discovery reportedly attracted 9.6 million viewers on the CBS broadcast network before the show was transitioned to the streaming service. Parrot Analytics subsequently reported Discovery was the second most streamed TV show in Summer 2017 (after Netflix’ Ozark), with 12.6 million average demand expressions, and was first for the week of October 5 through 11, with over 53 million average demand expressions.

Not a bad start, but by moving Discovery to the broadcast side this past year, CBS apparently signaled the show wasn’t building enough audience interest on the streaming service to offset the ad revenue losses from not putting it on the broadcast network — or, at least, that is how some TV insiders are interpreting the move. But, given Discovery’s broadcast ratings for the first season, it is unlikely the show is inundating the network in increased ad revenues either. It’s “linear” premiere broadcast on September 24, 2020 attracted 1.7 million viewers, placing it 8th out of the 12 broadcast network shows on that night — a bad start which has not improved over the next 13 episodes. [The most recent episode, broadcast on January 28, 2021, brought in 1.8 million viewers.]

Nonetheless, perhaps Discovery is at least attracting a new, younger audience for Star Trek? Uh, nope. Consistently, the show has achieved around a 0.2 rating within the 18–49 demo, which translates to about 280,000 people out of the 139 million Americans in that age group. That means the remaining 1.4 million Discovery viewers are aged 50 or older — in other words, old Star Trek nerds like me. How ironic would it be if it were the franchise’s original series fans that saved Discovery from cancellation, despite the show’s apparent attempts to distance itself from those same fans?

Doctor Who

No re-branding effort has broken my heart more than the decline of the BBC’s Doctor Who under showrunner Chris Chibnall’s leadership. The oldest science fiction series still on television feels irreparably damaged with its underdeveloped companion characters, generally poor scripts, and grade school level political sermons. The net result? The last two seasons featuring the 13th Doctor, played gamely by Jodi Whittaker, are more often boring than entertaining or thought-provoking.

But most regrettably, to lifelong fans who have loved the show since its first Doctor (played by William Hartnell), the BBC and Chibnall have taken the show’s long established canon, stuffed it in a British Army duffel bag, and thrown it in the River Thames to drown. And how did they do that? By rewriting the Doctor’s origin story — a Time Lord exiled from his home world of Gallifrey — in the fifth (“Fugitive of the Judoon”) and twelfth (“The Timeless Children”) episodes in the 13th Doctor’s second season, to where now the first Doctor is actually a previously unknown woman named Ruth Clayton and the ability of Doctors (Time Lords) to regenerate is now initially derived from a sadistic experiment on a small child who was the first living being found to have regenerate powers. If this story wasn’t so stupid, it would be sick.

Chibnall’s re-telling of the Doctor’s origin story was a WTF! moment for a lot of Whovians (the name often given to Doctor Who fans). But not a WTF! moment in the entertaining sense (like when half of The Avengers dissolved at the end of Infinity War), but in the bad sense.

Chibnall would have inspired no more controversy if he had gone back and rewritten Genesis 1:1 to read: “In the beginning Hillary Clinton created the heaven and the earth.” Such rewrites have only one purpose: to piss off people emotionally attached to the original story.

And that is exactly what the BBC and Chibnall have done — and many Doctor Who fans (though, as yet, not me) have responded by abandoning the franchise.

Result: The TV ratings history for the 13th Doctor’s two seasons reveals the damage done, though there was hope at the beginning. The 13th Doctor’s first episode on October 7, 2018, pulled in 10.96 million viewers — a significant improvement over the previous Doctor’s final season ratings which never exceeded 7.3 million viewers for an individual episode. However, in a near monotonic decline, the 13th Doctor’s latest episode (and last of the 2020 season) could only generate 4.69 million viewers, an all-time low since the series reboot in 2005.

And why did Doctor Who lose 6.3 million viewers? Because the BBC (through Chibnall) wanted Doctor Who to be more tuned to the times. They wanted a younger, more diverse, more socially enlightened audience for their show. Doctor Who was never cool enough. In fact, the original Doctor Who series was always kind of silly and escapist — a condition completely unacceptable in today’s political climate, according to the big heads at the BBC. Doctor Who needed to be relevant, so it became the BBC’s version of New Coke.

Except the BBC’s new Doctor Who is New Coke only if New Coke had tasted like windshield wiper fluid. From Chibnall’s pointed pen, the show has aggressively (and I would add, vindictively) alienated fans by marginalizing its original story.

Perhaps the Chibnall narrative is a objectively a better one. Who am I to say it isn’t? But the answer to that question doesn’t matter to Whovians who are deeply connected to the pre-Chibnall series. Whovians have left the franchise in the millions and unless the BBC has already concocted a Coca-Cola Classic-like response, I don’t see why they will come back.

Have TV and Movie Studios Forgotten How to Do Market Research?

The lesson from Star Wars, Star Trek and Doctor Who is NOT that brands shouldn’t change over time or that canon is sacrosanct and any deviations are unacceptable. Brands must adapt to survive.

All three of these franchises need a more diverse fan base to stay relevant and that starts with attracting more women and minorities into the fold. But how these franchises tried to evolve has been a textbook example on how not to do it.

In my opinion, it starts with solid writing and good storytelling, which requires better developed characters and more compelling narratives. Harry Potter is the contemporary gold standard. My personal favorite, however, is Guardians of the Galaxy — a comic book series I ignored as a kid, but in cinema form I love. Director/Writer James Gunn has offered us a master class at creating memorable characters, such as Nebula, Gamora, Drax, Peter Quill, Mantis, Rocket, and Groot. So much so, that a few plot holes now and then are quickly forgiven — not so with the re-branded Star Wars, Star Trek and Doctor Who.

Along with better writing, these three franchises have been poorly managed at the business level — and that starts with market research. Disney, Paramount and the BBC have demonstrated through their actions that they do not know their existing customers, much less how to attract new ones.

As a 2020 American Marketing Association study warns businesses:

“Any standout customer experience starts with figuring out the ‘what’ and working backwards to design, develop and deliver products and services that customers use and recommend to others. But how effective are marketing organizations at understanding “what” customers are looking for and ‘why’?”

The AMA’s answer to that last question was that most businesses — 80 percent by their estimate — do not understand the ‘what’ and ‘whys’ behind their current and potential customers’ motivations.

Does that mean these franchises would have been better off just engaging in slavish fan service? Absolutely not.

Fans are good at spending their money to watch their favorite movies and TV shows. They are not creative writers. Few people in contemporary marketing reference anymore the old trope of the “customer always being right,” as experience has taught companies and organizations that customers don’t always know what they want, much less know what they need. As Henry Ford is quoted as saying, “If I’d asked people what they wanted, they’d have asked for faster horses” [thoughit is not clear that he ever said that or would have believed it].

Instead, modern marketers tend to focus on understanding the customer experience and mindset in an effort to strategically differentiate their brands. Central to that process, the best organizations depend heavily on sound, objective research to answer key questions about their current and prospective customers.

There was a time when the entertainment industry was no different in its reliance on consumer data and feedback to shape product and distribution. The power of one particular market research firm, National Research Group (NRG), to determine movie release dates or whether a movie even gets released in theaters is legend in Hollywood. Though now a part of Nielsen Global Media (another research behemoth that has probably done as much to shape what we watch as NBC or CBS ever have), early in its existence the NRG was able to get the six major movie studios to sign exclusivity agreements granting NRG an effective monopoly on consumer-level information regarding upcoming movies. If you can control information, you can control people (including studio executives).

But something has happened in Hollywood in the past few years with respect to science fiction and superhero audiences (i.e., customers) who are perceived by many in Hollywood — wrongfully, I might add — as being predominately white males.

While men have long been over-represented among science fiction and fantasy writers — and that is a problem — the audience for these genres are more evenly divided demographically than commonly assumed.

For certain, the research says science fiction moviegoers skew young and male, but that is a crude understanding of science fiction fandom. Go to a Comicon conference and one will see crowds almost evenly divided between men and women and drawn from most races, ethnicities and age groups — though my experience has been that African-Americans are noticeably underrepresented (see photo below).

Similarly, a 2018 online survey of U.S. adults found that, while roughly three-quarters of men like science fiction and fantasy movies (76% and 71%, respectively), roughly two-thirds of women also like those movie genres (62% and 70%, respectively). The same survey also found that white Americans are no more likely to prefer these movie genres than Hispanic, African-American or other race/ethnicities.

Methodological Note:

Total sample size for this survey of U.S. moviegoers was 2,200 and the favorite genre results are based on the percentage of respondents who had a ‘very’ or ‘somewhat favorable’ impression of the movie genre.

The ‘white-male’ stereotyping of science fiction fans, so common within entertainment news stories about ‘toxic’ fans, also permeates descriptions of the gaming community, an entertainment subculture that shares many of the same franchises (Star Wars, The Avengers, The Witcher, Halo, etc.) popular within the science fiction and fantasy communities. Despite knowing better, when I think of a ‘gamer,’ I, too, think of people like my teenage son and his male cohorts.

Yet, in a 2008 study, Pew Research found that self-described “gamers” were 65 percent male and 35 percent female, and in 2013 Nintendo reported that its game-system users were evenly divided between men and women.

Conflating “white male” stereotypes of science fiction fans with “toxic” fans serves a dark purpose within Hollywood: The industry believes it can’t re-brand some of its most successful franchises without first destroying the foundations upon which those franchises were built.

In the process of doing that, Hollywood has ignited a war with some of its most loyal customers who have been

labeled within the industry as “toxic fans.”

A Cold War between Science Fiction Fans and Hollywood Continues

The digital cesspool — otherwise known as social media — can’t stop filling my inbox with stories about how “woke” Hollywood is vandalizing our most cherished science fiction and superhero franchises (Star Wars, Star Trek, Batman and Doctor Who, etc.) or how supposedly malevolent slash racist/sexist/homophobic/transphobic fans are bullying those who enjoy the recent “re-imaginings” of these franchises. All sides are producing more noise than insight.

In the midst of these unproductive, online shouting matches, there is real data to suggest much of the criticism of Disney’s Star Wars trilogy (The Force Awakens, The Last Jedi, and The Rise of Skywalker), CBS’ new Star Trek shows and theBBC’s 13th iteration of Doctor Who isrooted in genuine popularity declines within those franchises.

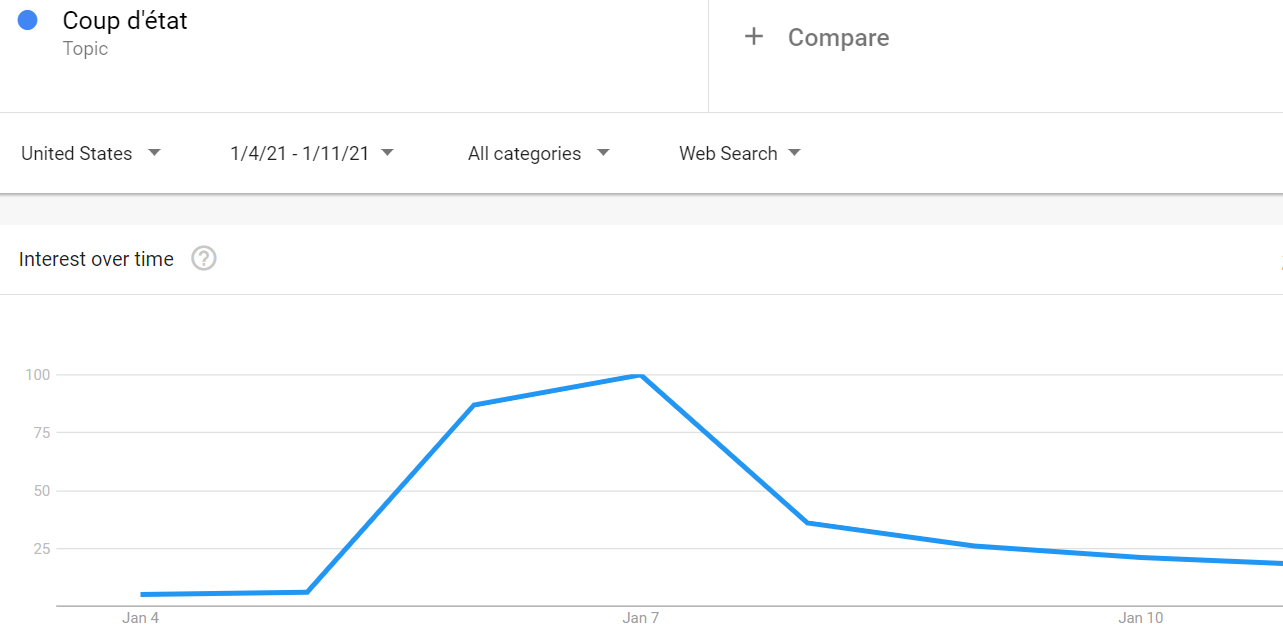

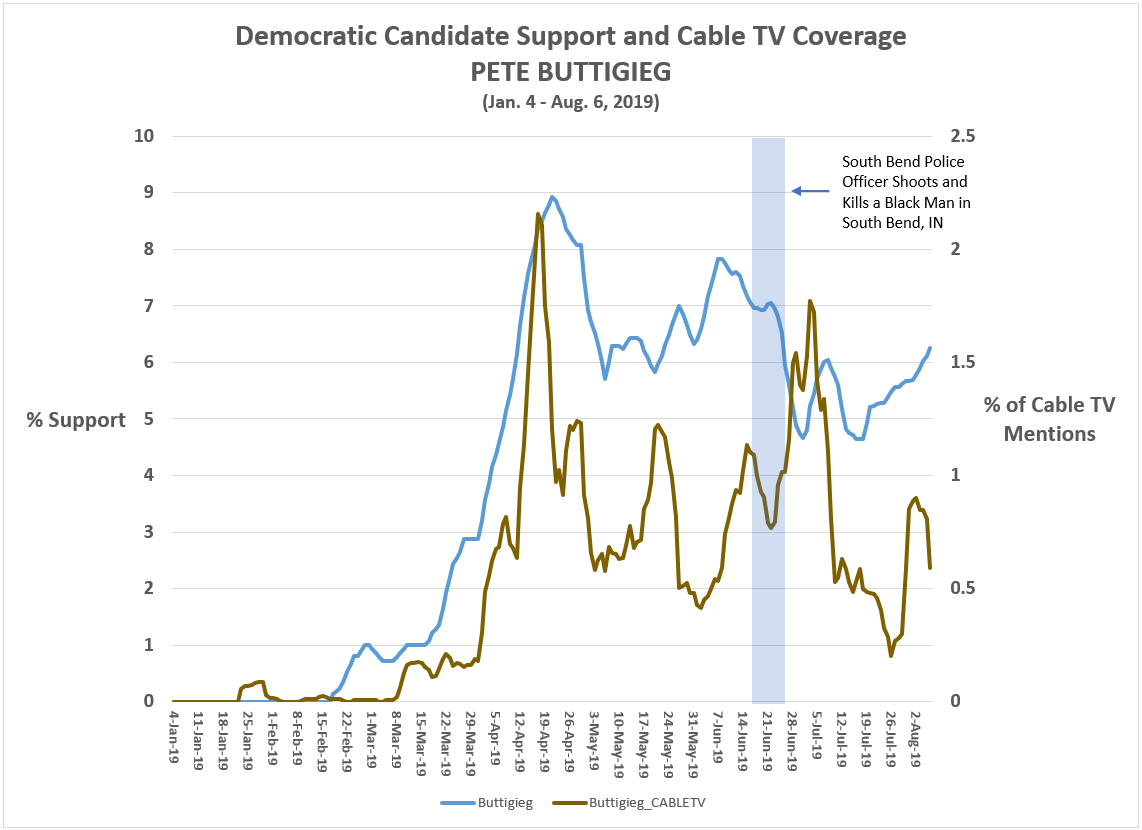

I produced the following chart in a previous post about the impact of The Force Awakens on interest in the Star Wars franchise:

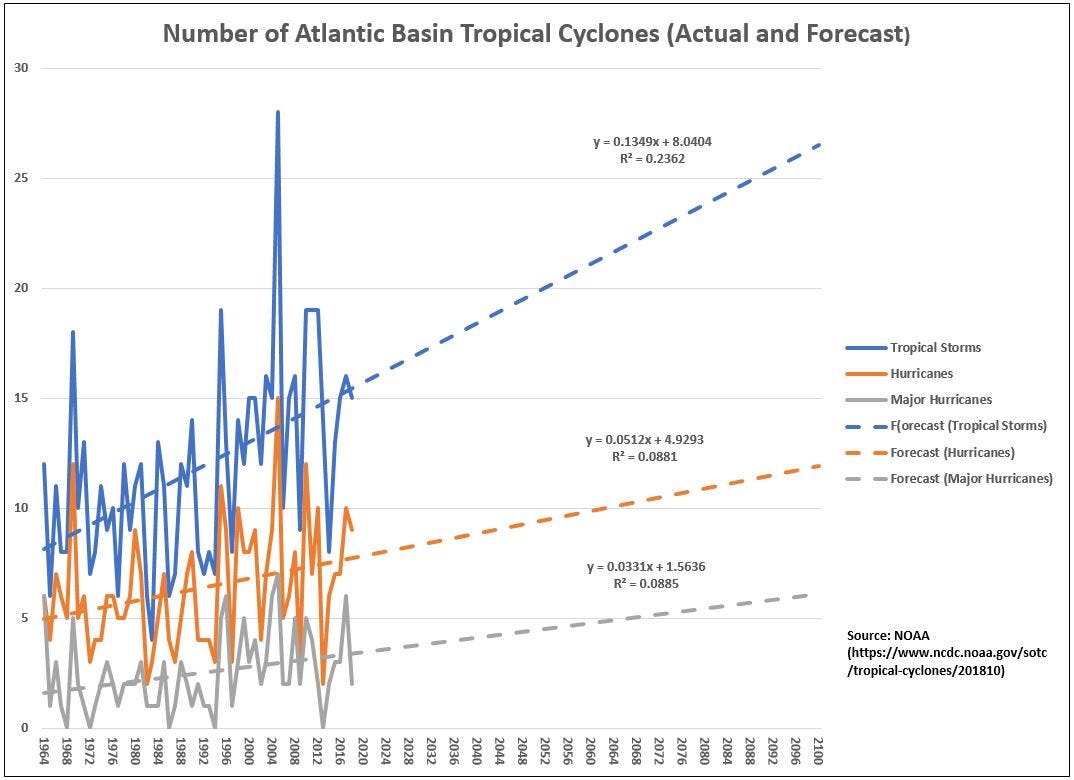

Figure 1: Worldwide Google searches on ‘Star Wars’ from January 2004 to May 2020

The finding was that the The Force Awakens failed to maintain the interest in Star Wars it had initially generated, as evidence by the declining “trend in peaks” with subsequent Disney Star Wars films.

A similar story can be told for some of TV’s most prominent science fiction and superhero franchises.

The broadcast TV audience numbers are well-summarized at these links: Star Trek: Discovery, Doctor Who, Batwoman (Season 1 & Season 2).

Bottom line: Our most enshrined science fiction and superhero franchises are losing audiences fast.

‘The Mandalorian’ Offers Hope on How To Re-Brand a Franchise

Whether these audience problems are due to bad writing, bad marketing, negative publicity caused by a small core of “toxic” fans, or just unsatisfied fan bases are an open dispute. What can be said with some certitude is that these franchises have underwhelmed audiences in their latest incarnations, with one exception…Disney’s Star Wars streaming series: The Mandalorian.

Methodological Note:

In a previous post I’ve shown that Google search trends strongly correlate with TV streaming viewership: TV shows that generate large numbers of Google searches tend to be TV shows people watch. A similar relationship has been shown to exist between movie box office figures and Google search trends.

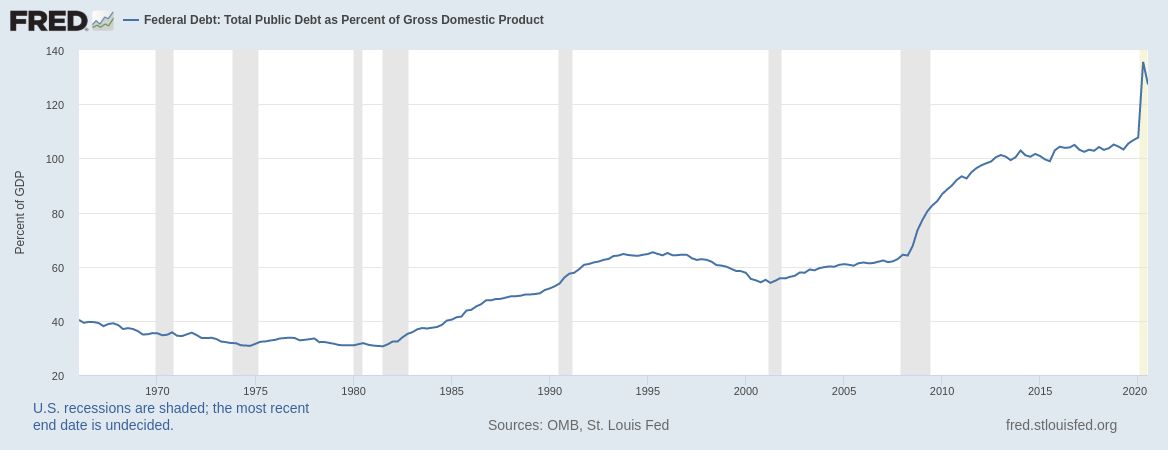

Figure 2 shows the Google search trends since September 2019 for Disney’s The Mandalorian. Over the two seasons the show has been available on Disney+ (Season 1: Nov. 12 — Dec. 27, 2019; Season 2: Oct. 30 — Dec. 18, 2020), intraseasonal interest in the show has generally gone up with each successive episode, with the most interest occurring for the season’s final episode. This “rising peaks” phenomenon — indicative of a well-received and successful TV or movie series — was particularly evident in The Mandalorian’s second season where characters very popular among long-time fans periodically emerged over the course of the season: Boba Fett, Bo-Katan, Ashoka Tano, and (of course) Luke Skywalker.

Figure 2: Google search trends for Disney’s The Mandalorian (Sept. 2019 to Feb. 2021)

It has only been two seasons, but The Mandalorian’s creative leaders — Jon Favreau and Dave Filoni — have been able to maintain steady audience interest, though they run the risk of eating their seed corn with the frequent fan-favorite character roll outs. It will not take long for them to run out of cherished and widely-known Star Wars characters. [Jon/Dave, I love Shaak Ti, but what are the chances she will ever come back?]

Nonetheless, The Mandalorian stands in stark contrast to some other science fiction and superhero franchises who have struggled to build their audiences in the past five years.

Figure 3 shows four TV shows with declining intraseasonal and/or interseasonal peaks. We’ve discussed Discovery and Doctor Who’s audience problems above, but Supergirl deserves some particular attention as my son and I watched the show faithfully through the first four seasons.

Figure 3: Google search trends for Star Trek: Discovery, Doctor Who, Batwoman, and Supergirl (Feb. 2016 to Feb. 2021)

Supergirl, whose title character is played bya mostcharmingMelissa Benoist, debuted on October 26, 2015 on CBS and averaged 9.8 million viewers per episode in its freshman season, making it the 8th most watched TV show for the year — a solid start.

Regrettably, CBS moved the show to its sister network, The CW, where it experienced an immediate drop of 6.5 million viewers in its first season there and another 1.5 million viewers over the next three seasons. [Supergirl has since been cancelled.]

How did this happen?

Before blaming the show’s overt ‘wokeness’ — women were always competent, while white men were either evil (Jon Cryer’s Lex Luther was magnificent though) or lovesick puppies — the spotlight must be turned on the CBS executives who decided to anchor the show to The CW’s other superhero shows (The Flash and Arrow) in an effort to help the flagging sister network. Their attempt failed and Supergirl paid the price.

At the same time, Supergirl didn’t build on its smaller CW audience and that problem rests on the shoulders of the show’s creative minds, particularly Jessica Queller and Robert Rovner, who were the showrunners after the second season.

First, what happened to Superman? Supergirl’s cousin, Kal-El, was prominent in the second season, but then disappeared in Season 3 (apparently, he had a problem to solve in Madagascar caused by Reign, an existential threat to our planet who Supergirl happened to be fighting at the time). Superman couldn’t break away to help his cousin?

I watched the Supergirl TV show because I was a fan of her DC comics in childhood and few realize that Supergirl comics, at least among boys, were more popular than Wonder Woman’s in the 1960s, according to comics historian Peter Sanderson. And central to her story was always her cousin, Superman. But for reasons seemingly unrelated to the sentiments of the show’s fans, Superman’s appearances after Season 2 were largely limited to the annual Arrowverse crossover episodes.

Fine, Supergirl’s showrunners wanted the show to live or die based on the Supergirl character, not Superman’s. I get it. But a waste of one of the franchise’s greatest assets.

Second, the script writing on Supergirl changed noticeably after Season 2, with story lines mired in overly convenient plot twists (M’ymn, the Green Martian, gives up his life and merges with the earth to stop Reign’s terraforming the planet? How does that work? We’ll never know.), and clunky teaching moments on topics ranging from gun control to homosexuality. Instead of being a lighthearted diversion from the real world, as it mostly was in its first two seasons, the show’s writers thought it necessary to repurpose MSNBC content. Supergirl stopped being fun.

What Lessons are Learned?

The most important lesson from Coca-Cola’s New Coke blunder was that mistakes can be rectified, if dealt with promptly and earnestly. It is OK to make mistakes. You don’t even have to admit them. But you do have to address them.

In 1985, the year of New Coke’s introduction, Coca-Cola’s beverage lines owned 32.3 percent of the U.S. market to Pepsi’s 24.8 percent. Today, Coca-Cola owns 43.7 percent of the non-alcoholic beverage market in the U.S., compared to Pepsi’s 24.1 percent.

With The Mandalorian’s success, Hollywood may still realize that burning down decades of brand equity earned by franchises such as Star Wars, Star Trek and Doctor Who is not a sound business plan. The good news is, it is not too late to make amends with the millions of ardent fans who have supported these franchises through the good, the bad and the Jar Jar Binks. That Star Wars fans can now laugh about Jar Jar is proof of that.

- K.R.K.

Send comments to: nuqum@protonmail.com